|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1969 (Part Three)

“The Chicago police were enraged that a church would open its doors to a black gang like the D’s, and Otis had to restrain one white cop from bulling his way into the church with his shotgun. The D’s quickly moved into the sanctuary of the church as they arrived.”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

During the summer Otis and I had some significant contact with the D’s thanks to the picketing at construction sites. Now the gang leaders came to Otis to ask if they could use the parish hall for a “call out meeting.” Their purpose was to try to put an end to the gang shootings on their recruitment drives. During the late spring there had been about two dozen such shootings with some fatalities. Unlike the Blackstone Rangers who had an organizational hierarchy, the D’s were a confederation of smaller gangs, often with antisocial modifiers like Vietcong Disciples, Devil’s Disciples, or Boss Pimp Disciples who loosely belonged to the Disciple Nation. Their slogan, spray-painted on many walls was, “D’s run it!” They now told Otis, “We want to be an asset to this community, not a liability.” We responded by telling them that there were certain rules they had to abide by if they used our facilities: no guns or weapons, no booze or drugs, no strong-arm methods and no disrespect of the church or anyone associated with it. Could a gang keep its word and reform itself?

About 500 D’s gathered in the church building on Saturday, October 11, 1969, a much larger turn-out than even they expected. The Chicago police were enraged that a church would open its doors to a black gang like the D’s, and Otis had to restrain one white cop from bulling his way into the church with his shotgun. The D’s quickly moved into the sanctuary of the church as they arrived. Those who tarried outside were lined up against the stone front of the church to be frisked by the police. It was a scene right out of the Gestapo handbook: 40 black teen gang-bangers leaning spread-eagle against the wall being searched from head to toe. The police didn’t find one weapon and couldn’t arrest anyone. We were able to keep the police outside the building. We feared that if they got inside, they would plant evidence to use for our arrest. Miraculously the day ended without further incident even though Harvard street was clogged with two dozen squad cars and disturbed by the continual whirl of helicopter blades overhead, often more than one. The gang leaders had worked out an understanding that would hold. There were no more gang shootings for quite some time.

The next Monday I attended the Northwest Pastoral Conference at Delavan, Wisconsin, and returned home on Wednesday. I had some work to do in the sacristy, and while I was there Les Woodard phoned. Les and his wife were black members who once lived near the church, but had moved farther south — a good middle-class black family generously supportive of the church. “Hey, where have you been?” Les asked in strident tone. “Have you seen the Defender? he continued. The Daily Defender was the black newspaper on the South Side, often given over to sensationalist journalism. I had Les read the headlines and story to me over the phone. On the front page in bold three-inch green type was the headline: “HOLD 200 AT GUNPOINT IN CHURCH.” On the third page was the story, only four column inches long (but enough evidence, the Defender judged, to warrant the screaming headlines), which began: “It was learned from reliable sources in the police department that members of the Disciples street gang held 200 youths at gunpoint in Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 6430 S. Harvard. ...” I tried to explain the situation to Les over the phone, and his only response was, “Brother, do we have problems!”

Needless to say the church phone started ringing off the hook. I responded to irate callers, telling them that no reporter from the Defender was ever on the scene, that they never called us for our response to the inaccurate and misleading police report, and that if, truly, 200 young male kids were held in gunpoint at any church, the governor of the state would certainly call out the national guard. The police had frisked the gang-bangers before they entered the church and found no weapons. Neither did we see any inside the church. So Otis and I worked overtime to piece together what happened. We were aided in our search by the 61st and Green Street block club, which sent a letter of protest to the “Lutheran Church, Missouri Synagogue, 77 W. Washington.” This address happened to be the address of the Northern Illinois District of the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod under whose jurisdiction we didn’t fall. But the letter threatened court action and a lawsuit against the church for “aiding and abetting the D’s and encouraging the kidnapping of innocent children.”

The Northern Illinois District office was so uptight and scared that they didn’t even phone us, probably believing us to be guilty as charged. They didn’t bother to check out the story, but sent the block club letter on to Pastor Bertwin Frey, president of the English District and my bishop, whose office was in Cleveland, Ohio. Bertwin Frey was a very understanding, trusting bishop; he thermofaxed copies of everything (including the cover letter sent by the Northern Illinois District president) back to me. Bert’s accompanying letter read essentially: “We know you have a difficult ministry. We don’t always know what you’re doing but we trust you. Please let us know the details when you work things out” (a paraphrase). I sent President Frey a full explanation. He wrote back:

“Thanks, Joel, for taking the time to fill me in on the recruitment incident. As you know, I have complete confidence in you. I am surely aware of the risky business in which you are involved, but I also know you can hardly afford not to take risks. In this very difficult situation I pray for you the continued guidance of our Lord! I know you’re giving the cause everything you’ve got. I ask no more. Stay strong! More and more blessings!”

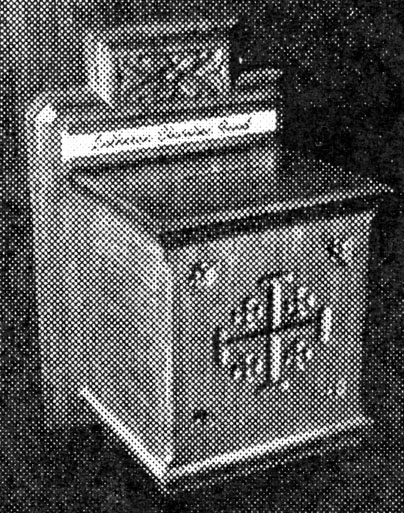

Might box

The Our Redeemer mite box received some strange offerings, including a live shotgun shell left by a Chicago police officer.

Otis and I made contact with the parents who sent the original letter and sat down with them. They were frightened of us at first, thinking we were in cahoots with the gang. It seemed like four of their children had been “recruited” to attend the call out meeting by force — the meeting that was supposed to do away with strong-arm gang recruiting. Otis recalled that on that Saturday afternoon the police did give him the names of four teens whose parents wanted them to come home. Otis read these names over the church’s loudspeaker and the boys left the assembly to the derisive hoots of “Mama’s boy.” But all four boys were reunited with their parents, and four is a far cry from 200.

Otis and I circulated freely among the D’s at the Saturday afternoon meeting and saw no weapons. Neither did the police find any weapons, not even a pocket knife. While we had no illusions that any of the gang-bangers were angels, it was the hostile presence of the more than two dozen police officers that was a more serious threat to the community than the potentially explosive nature of the call-out meeting. One of the cops left a “calling card” behind for Otis and me, which Otis found in the mite box inside the front door. The mite box had been forced open so often that we left it open and unlocked. It contained a live police issue shotgun shell. Some years later just after Our Redeemer closed, I was able to take a quick tour of the building, and found the mite box ripped from the wall, lying on the floor. I took it home with me, a relic token of this day when the Chicago police left a message that threatened our lives.

Some time later two officers from the state attorney’s office paid me a visit to find out what our intentions were. This was the first contact we had from anyone in an official capacity desiring to hear our side of the story. “We don’t want another First Presbyterian,” they told me, a reference to Pastor John Frey’s church in Woodlawn. They forcefully told me how evil gangs were and invited me to come down to their 26th and California office and speak to the chief gang intelligence officer. Instead Otis and I attended the meeting of the 61st and Green Street block club. The block captain told me that they never had so many residents out for a meeting as they did that night, and still the local residents were outnumbered by the plainclothes police, almost all of them white. Why they were in plain clothes I’ll never know; their white skin, age and demeanor gave them away.

We went to the meeting with the intention of enlisting community support in working with the D’s, but the police used every trick at their disposal to frighten the people. They told all manner of horror stories and the people finally refused to cooperate with us. We tried to explain that gangs are the creation of the ghetto and that it has always been this way in Chicago even with the white ethnic gangs. A gang functions as a substitute family — the benefits of belonging to a gang are a sense of identity, power, and protection. Gangs have a tribal culture — they have their own heros, saints (those who died in gang wars), and stories; they offer an explanation of the world to the members; they have a “map of the world” (the gang’s turf). Older gang members mentor younger members (novices or initiates) and help them out as big brothers. Where there is family and social dysfunction, the gangs function quite effectively according to their own code of conduct. Gangs are social scapegoats, a convenient excuse used by those who should be responsible for the health and safety of the community.

Chicago authorities are famous for their self-righteousness. Richard Daley once proudly claimed, “Chicago has no ghettos.” It is true that gangs turn violent, that they are guilty of taking lessons from the white underworld mob and selling protection. At this time the cocaine epidemic hadn’t yet hit the streets of Englewood and the D’s did not yet deal drugs. Otis and I learned a lesson: There is not much we can do in a positive way with the D’s unless we have community understanding and support. That was not forthcoming. When a multitude of people had saws, we didn’t want to be out on a limb. A couple of years later I heard Renault Robinson, head of the Afro-American Patrolmen’s Association, explain to Howard Miller on talk radio that “the black gang problem was caused by those white liberal ministers and foundations that wanted to invest in crime.” The whitey preacher is now the new scapegoat. Many of the gang leaders we knew back in 1969 are today either dead or in jail.

So Otis and I went looking for the gang leaders. We dropped in at their storefront center on 63rd Street but the leaders were never in. We left word: Call us. But they never did. They undoubtedly knew that we knew there had been recruiting going on leading up to the call-out meeting and that trust had been broken. We had helped them, and they put us in a huge bind.

I found their headquarters to be very interesting. On the large front window, outlined with the clouds of heaven painted on the glass, were listed the names of their saints — gang member who died in battle. The names were printed on crosses which had little wings attached. The inside of the storefront was marked by a cleanliness you didn’t find on the streets outside. There was a rather lavish pool table with a shaded light hanging above it in the center of the room. Located prominently on a side wall was a large reproduction of Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” — Jesus and his disciples in their “crib.” The gang was a community not unlike a congregation, perhaps even with a bit more cohesion and communal commitment.

We used to be able to consult with gang leaders. On more than one occasion Otis arranged for a “hands off” promise from them. Take a gang member alone and he is just another scared and lonely ghetto kid. The D’s were busted up for the time being in our area, but crime still went on unabated. The ghetto creates the gang; the gang doesn’t create the ghetto.

In the aftermath of our little attempt to work with the D’s a phone tap was put on the church’s phone. I would answer the phone with a warning that the line was tapped, and often the eavesdropper would create an electrical sound just to let us know he knew that we knew what was “going down.” He must have been bored out of his skull, for there were no conspiracies going on at our church, except for the welcome “breathing together” (conspire) with which we were blessed by the Holy Spirit. A parade of building inspectors paid us continual visits — and they didn’t have to look long to find building violations at Our Redeemer. We live in Amerika.

Next: The Chicago Memoirs of 1969 (Part Four)

|