|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1969 (Part Two)

“I raced out the basement door to the parking lot. The power lines from the main pole to our house were sending up huge clouds of black smoke, and fire was racing back and forth from the pole to the house, traveling down the side of the house along the power lines. In my stupidity I stood under the overhead wires and melting tar fell in my hair and on my shirt.”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

Intolerance in the congregation cut both ways. Tom Gieschen’s Kapelle Choir from Concordia Teachers College sang at the church on May 18. I remember the date for a number of reasons. Tom and I had carefully planned the choir anthems. This year they were singing some striking arrangements of Negro spirituals — “Wondrous Love” (Christiansen), “Brazilian Psalm” (Berger), and “Balm in Gilead” (Dawson). Tom and I felt that this would be a good way to introduce the music of spirituals into the congregation’s repertoire. After the worship service some of our black members loudly denounced the fact that whites would sing black music ... and soon a hornet’s nest was afire. A dinner hosting the choir had been planned, but when some white members started selling tickets to what I had billed as a free pot luck dinner and telling some of our black teens that they couldn’t eat without a ticket while ushering in the white choir without tickets, all hell broke loose. In church, yet. Tom had split the choir in two, taking half to another church and leaving the Our Redeemer half with a student conductor, so he wasn’t around to help. The Concordia students caught on to what was going on, but they were our guests. I tried moralistic guilt: “Okay, try to be good Christian people.” What did Jesus do when his disciples argued among themselves about who was the greatest? He found a child. And so Sue and I sat down to eat and surrounded ourselves with children, starting with Philip and his baby sister, Joy. Other kids joined us, hoping to hold the baby. The “adults” would have to fend for themselves.

But by the time I got home late in that afternoon, I was in a deep mood of depression. My ministry was a failure and the pastoral care I provided wasn’t enough to encourage unity in the congregation. I sat in the yellow rocking chair, the chair my maternal grandfather had in his parsonage study which I inherited and had refinished. I just stared at the wall, numb. Sensing that something was not right, Philip came and crawled up onto my lap and I hugged him so tight he might have been crushed. He was the only buffer zone between me and my suicidal thoughts. Sue paced the floor in the living room, worried about my mental state. And then the doorbell rang. I slowly went to the door and opened it. There stood a white man I didn’t recognize, holding out a white, sealed envelope. Now I knew from recent experience not to take such envelopes from strangers. The last time I did that just the day before, a sheriff’s deputy served me with papers, garnishing Will McCluster’s wages for the third time.

The man asked, “Are you Pastor Nickel?” I nodded. “Here,” he said, “I’m supposed to deliver this to you from a friend.” I hesitatingly took the envelope and the man seemed to disappear down the wide parsonage stairs. I closed the door and opened the envelope. Inside were ten crisp one hundred dollar bills. “Sue,” I weakly shouted, “I’ve just seen an angel. He left us $1,000.” Now, in 1969 that was a pretty penny. Its source was a mystery. It was heaven-sent, a visitation in the depths of my despair. We used the money sparingly. Some went for lumber and repairs on the church, some was used to purchase fabric for banners and paint for the parsonage basement floor, some went to Jewel Cherry who worked part time as our secretary, some paid for VBS expenses, some was given as a loan to Will McCluster and his nephew, Cleo Lake (never repaid), and some was used later that summer for plane fare.

On Pentecost we confirmed ten teenagers in their Christian faith, but three years later only two of the ten were still active with the church. A work crew from Grace Lutheran Church in River Forest helped to build walls on the second floor of the parish hall for a library room. Jim Puscheck, a friend from brother Mark’s Walther High School class living in Elmhurst, finished the job, sanding and painting. Jim frequently brought canned goods to our food bank and clothes for the free “clothes closet.” The largest cost was for the electrical wiring and lighting fixtures. I added wall shelving and put the books in order.

There were questions about what happened to the crucifix which had been on the wall on the first floor of the parish hall. Karl Schuessler, Paul’s brother, had been in church with his mother one Sunday and had taken the crucifix, which was a memorial to his father, Luther. To their credit, the Schuessler family knew the dynamics of the parish and had no wish to continue a “Schuessler mystique.” Karl also took down the Schuessler photographs that were on the wall as well, but I explained to him that the Ladies Aid would never believe me if I told them he had them, suspecting me of sabotage and petty thievery instead. Karl reluctantly put the photos back up and instead went home and sent a formal request to the Ladies Aid for the expensively framed photos. I later delivered the photographs to Karl and Paul at an English District Pastoral Conference after the Ladies Aid gave their permission. “Someone will only break the glass and damage the pictures and disgrace the memory of the Schuesslers,” one member stated. One church member missed the Schuessler memorial crucifix, thinking it had been stolen. When I explained that Karl wanted it as a memento, the inquirer was satisfied. I remember thinking, “at Our Redeemer, a Schuessler can do no wrong.”

In place of the crucifix I made a cross out of scrap lumber, a collage-like piece with different color wood stains, and a corpus made with nails. To one side of the cross I framed a George Rouault print, “Head of Christ,” and on the other side a print of a black Jesus. The cross drew expected objections, until I told everyone that it was “the old rugged cross.” Two weeks after the black Jesus picture was on the wall, a little child, Sylvester, threw a ball and broke the glass. I never replaced the glass, because for me it was a fitting reminder of the “great white picture controversy.”

We were using a lot of folk tunes in our worship — not exactly in the black idiom, but they did give our worship a contemporary ring. Wendell would take the “L” from River Forest to Englewood every Saturday night and stay overnight with us in the “maid’s room.” We told him that whatever he found in our refrigerator was fair game for his appetite. Wendell and I would then go over to the church and run through the songs and hymns to be used the next morning, deciding when to use the organ and when to use the fine grand piano. Wendell was proficient on both instruments, and played hymns with a Baptist flare. He was adept at improvising, so never played the hymns quite the same way twice in a row, which was a challenge when, before worship began, I practiced new songs with the congregation or had a chant line during the liturgy. It was an uplifting experience: the two of us alone in the cavernous church at night, with the huge organ playing full blast, blowing the dust off any surface in the church where it had settled. Wendell was good. But one Sunday morning when the youth choir sang a folk song with Bruce Chapman on the bongo drums, one irate member remarked, “If they play that jungle music once more I’m leaving the church.” The midnight jam sessions with Wendell always restored my energy with a heady shot of the Spirit. And Wendell, for his part, restored his energy at our refrigerator door.

June arrived and the hot summer was upon us. Everyone wondered just how “hot” it would get — and not just about degrees Fahrenheit. On June 17th Merv Marguardt, Joel Benbow, and Tom Spahn drove in from Iowa with their wives to plan the agenda for the youth gathering at Camp Okoboji later that summer. I was to be the theme leader with some of the Our Redeemer teens, a planned exposure between rural and city kids, white and black. The Tuesday afternoon was hot and there was a lot of activity out on the church parking lot. We were sitting in the parsonage living room discussing our plans when the lights went out. I went down to the basement to check the fuse box and found nothing blown. I looked out the window in the laundry room and saw billows of smoke. Thinking that a garage behind the church was on fire, I raced out the basement door to the parking lot. The power lines from the main pole to our house were sending up huge clouds of black smoke, and fire was racing back and forth from the pole to the house, traveling down the side of the house along the power lines. In my stupidity I stood under the overhead wires and melting tar fell in my hair and on my shirt. Someone yelled that they had called the fire department and I ran back inside the house to see if the fire was making its way inside. By then the fire engines had arrived and over 100 spectators had gathered. They sprayed the wires with foam and soon the wires dropped off the transformer.

Once the fire was extinguished we looked for the cause. The glass window in our meter had been broken and someone had dropped inside a large brass key. The brick wall of the parsonage was the backstop with a strike zone painted in white on the wall. When a wild pitched baseball hit the meter box it jarred the key loose which shorted out the two poles in the base of the box causing the fire. It meant no power for two days. The Iowa pastors had a fine ghetto experience and soon packed for their drive back to the corn fields. We transferred all of the food in our fridge to the church and spent the evening romantically by candlelight. Never a dull moment.

The following Thursday I flew to Lincoln, Nebraska to present a topic on urban ministry at Concordia Teachers College in Seward for one of their continuing education seminars. My primary focus was religious education in the city (by this time “R Is for Religion” published by Morse Press, Medford, Oregon, was in circulation as well as the colorful flip charts, “Say and Do Love,” published by Concordia). I put together a multimedia presentation (when the term was new) that included an 8 mm. color film of Our Redeemer, parts of the black and white 16 mm. “Martin Luther” film, color slides of Englewood, and transparent collage film for overhead projector that I had used at the previous Advent and Lenten vesper services at Our Redeemer. The background tape recording contained the sounds of the Englewood streets, with radios and sirens blaring. This was the first time in four years of marriage that Sue and I were ever apart for more than a day.

I flew back for the Sunday service, and that same evening had a speaking engagement at Good Shepherd Lutheran Church in Palos Park, where I showed examples of the church banners we were creating. When I arrived home that evening, Sue was doubled over in pain. I phoned Dr. Sharer out in Oak Park and early Monday morning drove Susan to West Suburban Hospital. I was scheduled to be in St. Louis for a Mission:Life workshop (the new extensive Sunday School curriculum was being written by pastors and teachers in the field, an outgrowth of a convention resolution submitted by the Central City Circuit of Detroit to the 1965 national convention ... which I had written). But Sue had gall bladder surgery instead. I’m sure that the tensions under which we live were in part responsible for the gall bladder attack. Sue made it through the extensive surgery (laproscopic gall bladder surgery hadn’t been invented yet), pale and weak, and her recovery was slower than when she gave birth to Joy just the year before.

I drove to the hospital parking lot across the street and stood next to the VW bus with Philip in one arm and Joy in the other. They could see and wave at their Mommy in the window, since hospital rules didn’t allow children visitors on any floors. We were able to visit in the hospital lobby and Susan was able to gingerly hold her children on her lap. That was healing medicine. When I returned home that night with Philip and Joy, I found out that Hilmar Sieving was in the hospital again.

Vacation Bible School used the flip charts. “Say and Do Love” was a two-week program based on some of Jesus’ parables and miracles. Its inner dynamic was “visual communication,” and the opening, inductive question was always, “What do you see?” Wendell’s lively piano work was the high point each evening and we usually sang for 40 minutes every session. Each weekend that summer a member of the congregation would drive some of our children and teens to Camp Concordia in Gowen, Michigan.

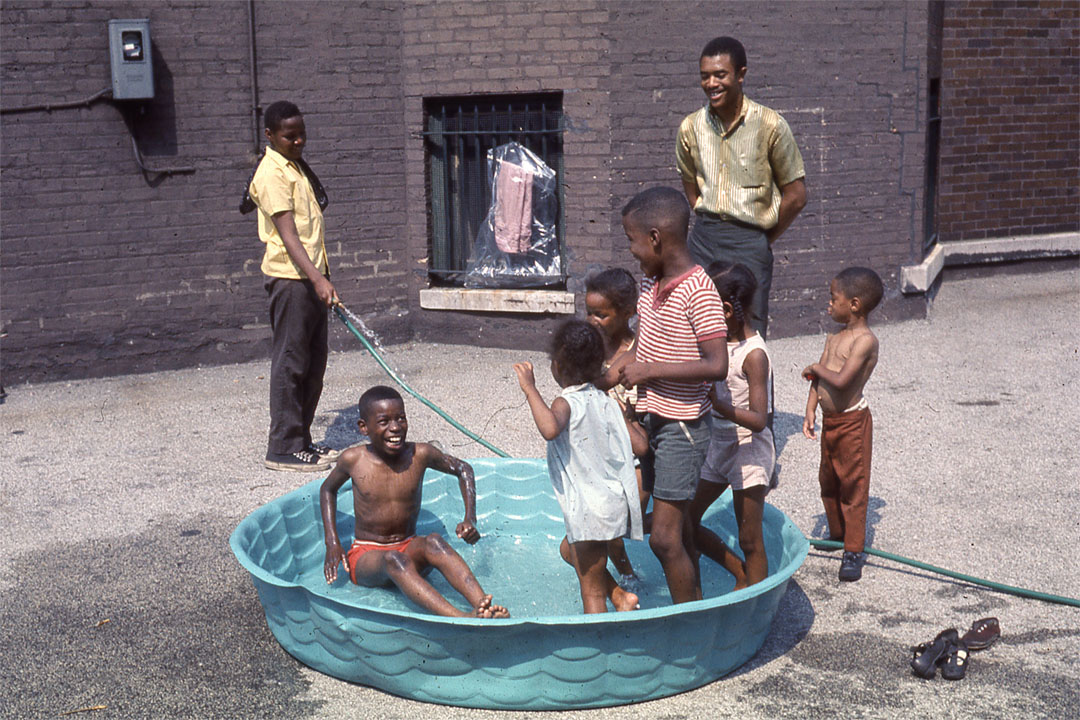

Wendell Clark supervises the parking lot wading pool underneath the parsonage living room window during the summer program.

Otis Flynn and Emma Guhl were elected as delegates to the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod national convention in Denver, where delegates from black Lutheran congregations attempted to have some influence. But the conservative power play was stronger, electing Jack Preus, bringing to an end all hope for creative mission growth in the Missouri Synod. The Lutheran Action Committee contingent was sorely out-numbered and never regrouped after the Denver convention. Even some of our moderate friends were quite critical of LAC, stating that the protests against the Vietnam war and our “ecclesiastical disobedience” of open communion hurt the cause, led to a backlash, and helped elect Preus. My response was to state that the “radical Lutherans are much more the ‘sons of the Reformation’ than those who opt for the status quo.” Where would the Lutheran church be without the freedom of the Gospel and the social conscience that goes with it? “Radix” is the base term for radical; it means “root,” and the deeper the singular root grows the truer its cause will be.

This was also the summer of black picket lines at construction sites in Chicago. Labor unions in Chicago had a limited quota system for admitting blacks into apprentice positions, which was a source of the limited employment opportunities for black men. Some of the civil rights organizations like Breadbasket were using black teen gang members to man the picket lines. Thanks to Otis’s contacts, some days I was enlisted to drive members of the D’s around to various construction sites on the South Side. That summer the D’s in Englewood and their rivals, the Blackstone Rangers in Woodlawn, had reached a temporary moratorium, united by a common cause against the racially restrictive trade unions. I was even driving the D’s around on Ranger turf, and once was ticketed by an over-zealous officer.

By August our appointment with Camp Okoboji in Iowa drew near. I visited Hilmar at Pat Wilcoxen’s home where he stayed while out of the hospital. Hilmar was one of the patients interviewed by Elisabeth Kiebler-Ross at Billings Hospital while doing research for her book, On Death and Dying. On this day Hilmar and I celebrated the eucharist together and shared the peace of the Lord. The loss of Hilmar loomed large on my anxiety index. But Hilmar was living for the day when Cathy would return from her trip to Europe, and expressed relief that his responsibilities for Johnny were over. He valued these last years during which he grew closer to Cathy — he thrived on the youthful enthusiasm of his daughter and her friends and knew that she had attained a self-sufficient level of maturity. He was proud of his daughter and anticipated meeting his son again, healed from their physical weakness. Wayne Saffen was also ministering to Hilmar. He encouraged me to go to Iowa.

So the four Nickels, Jerachael and John Pierce, Orlando Jackson, Karen Dockery and Greg Armstrong packed into the VW bus for the long drive to Camp Okoboji. Sue was a master at entertaining kids on long trips. She assisted me during my vicarage year at Riverside when we took a bunch of teens to Florida for spring break in the red Ford Econoline van the church owned. Later that summer, we took another such group to New York City for the World’s Fair. Sue was a trooper, which is one reason I married her. There were other reasons too. ...

We arrived in the northwest corner of Iowa late at night in a fierce electrical storm. A tornado had preceded us. Put five animated black teens in the midst of some white teens whose urban experience was nil, and watch the interaction. It was positive and exciting, and our black teens captivated the whole camp. We led discussions on poverty, over-population, and world hunger. Joel Benbow and I devised a socio-drama to physically demonstrate the problem by crowding four-fifths of the kids onto a little stage in the basement of the dining hall (they represented India, China, and Southeast Asia) while the other small groups gathered in the large basement hall (they represented the USA, USSR, Japan, and Canada). The small groups were given diplomatic, economic, and trade problems to solve in their nation’s self-interest while the larger group of kids on the stage yelled “help” at the top of their lungs. To further mess with their minds, the small groups were told they had just 30 minutes on the doomsday clock to solve their problems before “the bomb” went off. The pastors who served as camp staff, were assigned the role of the United Nations. The “problem” was solved before the 30 minutes elapsed when the developed nations realized that they had to deal with the four-fifths of the world population and offer help, symbolized by giving a cup of cold water to each person on the stage. It was a very educational experience.

That night we received word that Hilmar had died. Cathy came home just in time to help take Hilmar back to Billings Hospital. His funeral was set for Thursday at Our Redeemer, so Joel Benbow drove Sue, Philip, Joy, and me to the airport at Sioux City and we flew home (we could afford the airfare, thanks to the “angel” with the gift). Sue’s mother met us at the airport. She and Hilmar had been good friends. About 250 people attended the funeral, and the great cross-section of people was a tribute to

Hilmar’s life and friendship had enriched many — people from the university and from the ghetto, people working on mental retardation and education research, librarians and medical professionals, people from church and secular society both rich and poor. Pastor Wayne Saffen conducted the liturgy. Pastor A.R. Kretzmann led a private service in the morning for the family. John Mitchell, a social worker and lay leader at Our Redeemer, Hans Spalteholz, a doctoral student at the University of Chicago and professor at Concordia College in Portland, and Dr. Joseph Sittler, learned theologian still teaching at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, read the lessons. Wendell opened the organ up full blast and we offered our praise to God for the life of Hilmar Sieving. The sun shone brightly through the stained glass windows. I’ve never, ever felt deep emotions like this while preaching, but the Spirit sustained me and the word was proclaimed. Hilmar was buried next to his wife in the St. Luke Lutheran Cemetery on the North Side, where Sue’s grandparents and mother later would also be buried.

We invited Cathy to fly back to Iowa with us and she was happy to be among good friends. Everyone at Camp Okoboji embraced Cathy because there is a profound link between people of faith who live in the hope of Christ’s resurrection. Saturday when we packed up for the long drive back to Chicago, everyone parted in tears — the sharing had been so deep.

Eight of our teens went camping for a weekend toward the end of August at the Indiana Dunes, together with the Walther League from Grace, River Forest. They supplied all the equipment; we supplied the integration. June Feipel was along and slept in our large canvas tent with the girls. Sue, Philip, Joy, and I slept in our VW “camper” next to the Lueking’s camper. The nights were cold but the days were hot, and our spirits were revived. Our two-week vacation this year took us out West again, this time to deliver Sue’s sister, Nancy Koetke, to Reno, Nevada, where she had a gymnastic scholarship to attend the University of Nevada–Reno. Their mother, now called “Grammie” by grandchildren, was also along. We stopped overnight in Boulder, Colorado, to visit Roger and Vicki Schultz, having driven straight through from Chicago to Boulder in 26 hours. Nancy slept all the way. We drove into the Rocky Mountains and camped overnight at Yampa on a windswept hill, at a campsite that would years later lend its name to our model train layout: “Champaign, Yampa and Western RR.” The next morning Philip and I caught a couple of small trout, but we quickly ran back to camp when a sudden mountain storm was upon us.

We broke camp in 15 minutes and drove away from the campsite just as the snow came in gusts. Our guests of honor in our “campmobile” didn’t take too well to the harsh conditions. We drove straight through again, Yampa to Reno in 26 hours, stopping in Salt Lake City for new tires. After delivering Nancy, we camped at Lake Tahoe for a few glorious days (we had the lake to ourselves, as it was after Labor Day and the tourist season was over). On the way home we camped in the Tetons (the spaghetti dinner in the rain under the plastic drop cloth was colorful, with Philip painting his face with spaghetti sauce). We also took a side trip up to Mankato and Janesville, Minnesota, to revisit Joel’s childhood memories and the rural church where his grandfather was pastor for many years.

Fires, vandals, enterprising recyclers, desperate tenants — it all led to hollowed-out, abandoned skeletons of buildings. ");

print ("The stench of wet, charred wood formed a strong memory, which a cup of Lapsang Souchong tea could bring rushing back.

Church attendance this fall fell dramatically to the low 70s, and many people were losing heart. The congregation started to “go on welfare,” receiving a subsidy from the mission board of the English District for the first time. We were on ADC — aid to dependent churches. The apartment building across the street from the church had a fire in one of the third-floor apartments and the resulting water damage drove out five families. While the firemen were pulling their hoses down the stairs, we were walking up the stairs to recover soaked belongings. Water was running everywhere, cascading like a waterfall down from above and soaking our clothes. I got a good taste: It resembled a smokey Chinese tea I later had, which I called EBB tea: Englewood Burning Building tea. We stored some of the soaked and smokey furniture in our parish hall until the families could relocate. Here was another vacant building to contend with, waiting for the bulldozers.

Bill Schmidt came during the week and we continued work on our Mission:Life curricular assignment: seventh- and eighth-grade Sunday School lessons, “Moving through the Good Year”. We would try out our writing, songs and illustrations on the kids in our parishes — at Bill’s storefront church on Gratiot Avenue in Detroit and at Our Redeemer. We flew back and forth, often landing at Meigs Field on the lakefront in downtown Chicago. We knew the editors at Concordia Publishing House would have their red pencils ready for our “ghettoese” language and illustrations. So we gave them stuff we knew would be cut in order to protect other stuff, like the lesson, “You can’t be a half-assed Christian.” Jack Preus was already putting pressure on the Board for Parish Education and Concordia Publishing House, hoping to destroy the Mission:Life curriculum. Our material would be severely edited.

Otis and I drove out to Concordia in River Forest to recruit students for the fall tutoring program, and I preached at a chapel service there. I began the monumental task of sanding the floors in the parish hall, manual labor being a good change of pace for a clergyman. It was more work than I had anticipated, and dust was everywhere.

Next: The Chicago Memoirs of 1969 (Part Three)

|