|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1972

“The one thing Englewood and the University of Illinois had in common was transiency, a parade of people always passing through. Both places had a committed core of people who gave the two places a bit of consistency. Both places depended on district financial subsidy. My continued effectiveness at Our Redeemer was questionable without Otis; my abilities in an academic setting were untried.”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

Our January seminars this year centered on youth problems in Englewood. The Redeemer Royals were serious about attending church, usually sitting together, filling up a couple of the long pews in the center section. If one of their group was an acolyte, they would critique his performance, and woe to the Royal whose wick went out before he got the candles lit. That was no easy task, since wind currents in the chancel could be tricky due all our broken windows. Since the Royals were not exclusively a male club, we had female acolytes as well, and they too were subject to close scrutiny, though for different reasons.

My experiences at Chicago Academy were rewarding and slowly I began to discover a painting style all my own — abstract, geometric, exploring color and paint application techniques. I think it was Picasso who suggested that the process of creating a painting was an antidote to death, giving life to a canvas that would then have a life of its own. My art was an antidote to the dissipation of Englewood. In the process of painting I could decide to control the process or let it be spontaneous and unplanned. Not so in Englewood. My life was centered in our family — with Sue, Philip, Joy and Daniel — and I had to let everything else go its scattered way. Philip wanted more of my time, mimicking shaving at the bathroom mirror, using lots of shaving cream; when I didn’t pay attention to him, he would counter that by an assertive act, like taking a scissors to my brown short sleeved shirt and black satin “smoking jacket.”

Philip liked to go down to the parsonage basement and nail together the scraps of wood left over from some of my projects. He wouldn’t let us throw any of his “constructions” away. He had names for every piece and knew what they were long after he made them, although his parents couldn’t figure out how his imagination could be so precisely remembered. One evening I was working on a project in the basement. Philip was also building a construction next to me and spilled some nails all over the floor. I yelled at him, a momentary case of misplaced anger which he didn’t deserve. He ran upstairs, crying. I felt guilty about my outburst, and tiredly sat on the bottom basement step trying to figure myself out. Soon I heard the sound of little steps behind me. It was Philip, bringing me my pipe as a peace offering, saying, “I promise never to say ‘Save your lungs’ again.” I hugged him; at the age of 5 he was better at reconciliation than I was. The pipe offering, though, probably came at the instigation of his mother, who was keeping a loving eye on both of us. As Picasso also said, “It takes a long time to become young!” I could still learn a few things.

Community ministry

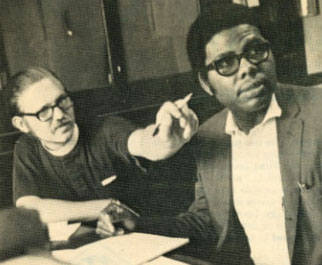

Joel and Otis Flynn at a meeting in the Our Redeemer parish hall.

The wind was quite strong that night (65 m.p.h. the weather report said). It blew tin cans across the parking lot and banged the broken French windows in the building across the street. It was an eerie sound, an abandoned city swept by high wind. Few people were on the street, and because of the plunging temperature, the VW bus probably wouldn’t start in the morning. Otis informed me the next day that he had accepted a new job with a community center in East Chicago Heights. The salary was double what he made at Our Redeemer and I figured Otis needed some growing room in a new setting just like I needed the creative edge at CAFA. But Otis would be impossible to replace: his dedication, insight, energy and concern for poor people in an often thankless job among often stressed-out people was impressive. But Otis too had his limits, and was also considering marriage. People with constant needs from so many directions wore us down. Krager was in town again badgering me to bring him $10 downtown because he was afraid to take the “L” out to Englewood. One of the “regulars” came to the parsonage door, saying he needed food for his crying baby. I nicknamed him “the stickup man” because every time he realized his “con” story wasn’t working, he turned and angrily said, “Well, I’ll just have to go out on the street and pull a stick-up,” as if the guilt would be mine for contributing him to the Englewood crime wave. If you know you don’t have baby food in the house and have a hungry baby, why do you wait until 9 p.m. to go begging for help? The Englewood Urban Progress Center closes down at 5 p.m. every weekday when all the “healers” go home. It occurred to me that I was becoming “a burnt-out case.” Maybe next time the “stick-up man” will come earlier.

There were still moments of humor to keep me humble and happy, if I didn’t take myself too seriously. Usually every morning Oliver Carter had to tow my VW bus down Harvard Avenue and I would pop the clutch to get it started, illegal according to city ordinance, but I didn’t have money for a new battery yet. This morning was no exception as the temperature fell to five below zero. As I was pushing the bus down the driveway and onto the street, two of the men from the corner came by. “You helped us so we’ll help you,” they stated, mimicking the poster on Otis’ office wall. They put their shoulders to the back of the bus and pushed it into the middle of Harvard Avenue and attached the tow rope. Because of the ice and my 20 weight oil, it took Oliver two blocks before the bus started.

Instead of taking my normal battery-charging run down the Dan Ryan, I decided to drive over to the lumber year and buy some plywood to board up the window to the old coal bin which had been violated three night previous. No food had been stolen; someone broke in just to get warm. I stopped to get gas, then drove west on 59th Street. Close to the railroad viaduct, the same two men who had helped push the VW saw me coming and stood in the middle of the street to flag me down. I stopped and they got in. The older of the two men was walking over to Evangelical Hospital to pick up the baby pictures of his niece; the younger of the two had been drinking and was high. When we stopped at the hospital he stayed in the bus to rap with me. “Why are white people so prejudiced?” he asked. He wasn’t interested in my socio-psychological answers, just in asking questions to see if he could make me uptight. Questions like this kept coming at me as we drove over to the Hines Lumber yard west of Ashland, across the racial divide. “Why don’t we have the right to live in this neighborhood?” the high one asked. “We can live anywhere we want,” the elder of the two stated, playing the moderating influence. “Sure,” was the answer, “and invite the cops to bust us over the head. Civil rights ain’t actual rights.”

They insisted on following me into the lumber yard office, intentionally becoming obnoxious, using the washroom to take more sips from their brown bag-concealed bottle of wine. When one of them requested a towel, made available by the office to clean off windshields, and cleaned his shoes with it, the clerk snapped. All of a sudden he couldn’t find Our Redeemer’s credit account. I didn’t have any cash on me. After 15 minutes when the clerk saw I wasn’t about to leave with my two black friends, he conveniently found the charge account and filled my order. My two friends carried the plywood sheet out to the van in an unsteady gait, having to exit through two swinging doors, one of them walking backwards, carrying the “white man’s burden.” With the plywood loaded we headed back along 59th Street. “Back to the old neighborhood,” I quipped. The elder of the two told the younger one to sit in the back of the bus because he “hadn’t been freed yet.”

Then he turned to me. “Say, man, why you got that beard?”

“To show that I don’t work for the city, state, or police,” was my answer.

“You mean you’re a hippie?” “No,” I answered.

“He’s a priest,” said the one in the back of the bus.

“Then how come you got children?” the elder asked. “How’d you get away with it?”

“Because I’m not a Roman Catholic. I’m a Lutheran,” I explained. “Loot...loot who?” the elder asked, confused. “I’m just a plain Protestant,” I tried to clarify.

“So you are a protester? Just like all those hippies!” he finally concluded. The only connection the word “Lutheran” had in Englewood was the part of the name we shared with Martin Luther King Jr. It was enough to open some doors.

I dropped them off at the corner of 63rd and Harvard where the drug store doubles as a liquor store. When one of them noticed my disapproval of their upcoming purchase, he said in a parting shot, “Don’t worry, it’s for my mother. She’s sick.”

On Friday night, January 28th, I received a long distance phone call from the president of the Central Illinois District, Rudy Haak. He informed me that I would be receiving a pastoral call to become co-pastor in the district’s campus ministry at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. Ray Eissfeldt, pastor at “the Chapel,” also phoned a few nights later with more information. Ray’s wife, Eleanor, had terminal cancer, and Ray needed support. We drove to Champaign on February 4 to look the place over. The facilities were impressive. The LCMS through its districts had invested wisely in campus ministry after the end of WWII, building chapels and student centers at all the Big Ten Universities. But how could I abandon Our Redeemer? It wouldn’t survive both Otis and myself leaving at the same time. My leaving would be its final demise.

The one thing Englewood and the University of Illinois had in common was transiency — a parade of people always passing through. Both places had a committed core of people who gave the two places a bit of consistency. Both places depended on district financial subsidy. My continued effectiveness at Our Redeemer was questionable without Otis; my abilities in an academic setting were untried. Our children listened intently to their parent’s conversation. Philip was opposed to moving, but his resistance mellowed when he realized he might be able to have a dog in Champaign. He insisted that we move all of his “constructions” as well.

Our family had the flu bug for a whole week, just at the time when we needed clearheaded thinking and energy. I didn’t enroll for the spring semester at CAFA with our decision up in the air. At this point in the “hood” it was a race between the bulldozer and the fire department to see how buildings came down the fastest. Richard Nixon had offered 2.5 billion dollars to rebuild North Vietnam if the Viet Cong would agree to a peace treaty, which led columnist Art Buchwald to suggest that we import “those North Vietnamese cats” to one of our urban ghettos to continue fighting, so that perhaps Nixon might make such an offer to US cities. Buchwald: “No one gives a damn about the hearts and minds of the people in the ghetto because there are no Commies there. If Nixon’s willing to pay the North Vietnamese $2.5 billion to get out of South Vietnam, there is no telling what the President will offer them to get out of Washington DC.”

I accepted the call to Champaign on February 20. Tom Gieschen, who was the only person to emphatically encourage me to stay, told me, “Most of the people figured you’d take the call; what puzzled them is that it took you so long to decide.” We committed ourselves to stay at Our Redeemer until Easter, trying to set up some transition arrangements and find new staff people. I still had ten Redeemer Royals to confirm. Jim Hawthorne agreed to a contract to serve Our Redeemer as pastor under the circuit counselor’s supervision.

On Maundy Thursday we had a very moving service in the parish hall around a table. There were about 40 people present, and we baptized Albert Lee Jackson, Michael Tyrone Lyons, and Kell Dawson. Albert Lee used to give us the most trouble of any kid on the block, although his sister ran him a close second. We watched him grow up during our five years in Englewood. Whenever there had been a break-in, Albert Lee was the one I’d try to track down. But this night these young men were serious, intent on being part of the Christian community and letting their “Gospel lights” shine. It wasn’t easy to encourage the people when I was moving away, and I was trying hard to convince myself this wasn’t a cop out.

Our Easter celebration of Christ’s resurrection was an event mixed with joy and sorrow. The Royals constituted the second largest confirmation class that I had at Our Redeemer and could be the foundation for a vigorous youth ministry. After their confirmation, everyone went home and we were alone again in the parsonage. That too had a message, that maybe our time to leave had come, and the Spirit of the Lord was inviting us to move into a new chapter in ministry. We would forever take the lessons of Englewood with us. The parsonage, once we vacated it, would be used by a program to care for mentally handicapped children, since Jim Hawthrone and his wife already had a residence. Hilmar Sieving would be pleased.

On Monday the moving van arrived to pack up our earthly goods. Having received a phone call from the police’s stolen merchandise warehouse, I quickly drove over there to collect my slide projector. When I returned, in the mess of moving, little Joy came over to me, tugged on my shirt, and asked, “Daddy, when are the bulldozers coming?” She had been a child of the ghetto too long, at her young age observing that when people in our neighborhood moved out, their abode was torn down. I assured her that we’d leave the house standing tall. Many years later my children and their mother returned to 6418 South Harvard Avenue and had their picture taken on the parsonage steps.

Two weeks after we moved into our new home in Champaign, the anti-war protest at the University spilled over into the streets. There was a small riot at the National Guard armory and some downtown stores were trashed. Windows were broken, some stores were looted, and the “riot” made the five o’clock news in Chicago, prompting our friends, Don and Carolyn Becker to write us: “Wherever you go, you start riots.” We felt right at home.

Next: Postscript: The Chicago Memoirs

|