|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1971 (Part One)

“[The district police commander] ‘explained’ the stop-and-frisk rights that cops had. ‘You could be picked up anytime too,’ he told me to illustrate his point. ‘On what grounds?’ I asked. ‘Look, you’re suspicious. You’re white, and any whites who’re in the neighborhood after dark must be here for immoral purposes!’”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

Our Redeemer had a committed remnant of people still eager to serve despite all the difficulties we had encountered both by our Sunday congregation and our weekday congregation. Those whose membership was an exercise in nostalgia had transferred to other parishes. For many years the number of funerals had outnumbered baptisms in our yearly statistics. Often treacherous Chicago weather conditions made travel difficult for the commuter congregation. One Sunday in January our attendance dropped to 38, and that’s counting pregnant women like Sue twice. My ‘bishop’ Dave Eberhard had a saying: “if you can’t convert ‘em, conceive ‘em.” I was trying on both counts. I put an announcement in the bulletin: “Yesterday was experience, tomorrow is hope, and today is getting from one to the other as best we can.”

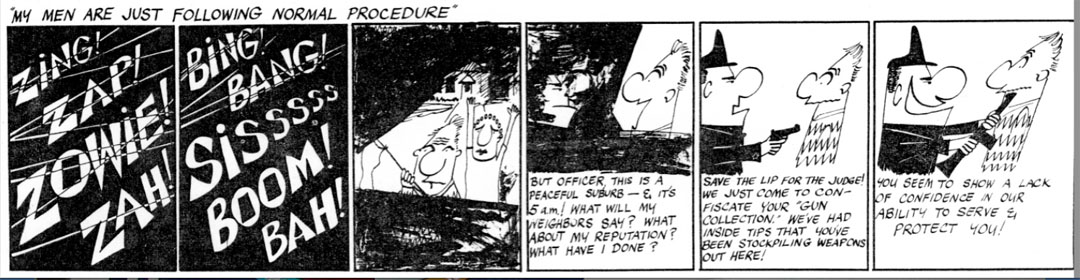

Getting from one to the other isn’t always an easy transition. You have to get past midnight first, as I experienced on the night of January 26 (actually the early morning of the 27th). I was hauling our garbage cans out the parsonage front door, placing them on the curb for the Wednesday morning garbage pickup. It was already 1 a.m. and five degrees below zero. As I tiredly ascended the front steps after placing the last container on the curb, I heard, then saw, a black Chevrolet come racing down Harvard Avenue, slamming on its brakes by the church parking lot driveway. There were no special markings on the car. Two white men darted out both front doors simultaneously, running in a crouched position with guns drawn toward the sidewalk just 30’ from where I was standing on the parsonage steps. “Stop! Police officers!” they shouted. The lone young black man stopped in his tracks as they surrounded him. They made him put his hands on top of his head and frisked him roughly. He didn’t have a wallet and seemed to have no identification. “Hey, what do you want?” he cried. They frisked him again, grabbing his genitals. “Keep your fuckin’ mouth shut,” one of the white men shouted as they threw him spread eagle over the trunk of the Chevrolet. They frisked him again in the same manner. “He doesn’t have an ID,” one said, but then, neither did either of the white rogues who claimed to be police. “We’ll have to take him in,” replied the other. They threw the black man into the back seat of the car, jumped in and sped off into the night. Stepping down to the sidewalk, I had the presence of mind to note the license plate number of the car. I had witnessed numerous stop and frisk maneuvers before, but nothing ever like this.

I walked up the parsonage stairs. Sue was standing inside the front door in her bathrobe. I described to her what I’d just witnessed, then went upstairs to put on my clerical collar, my identification badge. I told Sue that I had to do what I had to do. I got into the VW bus and drove over to the Englewood Police Precinct headquarters. The black Chevrolet was parked in the side driveway outside the station house, and the license plate matched the numbers I had memorized. I entered the all but deserted station and walked up the short flight of stairs to the front desk. I asked the desk sergeant where the plainclothes officers were who had just come in with a prisoner. He looked at me blankly. “No one has just come in with any prisoner,” he stated bluntly. “But,” I protested, “I just saw them make an arrest a few minutes ago. Their car is in the driveway outside.” “Look,” the sergeant retaliated, “no one’s brought a prisoner in here in the last hour.” He didn’t take very kindly to my clerical collar nor to my challenge to his authority and credibility. “Go look for yourself in the lock-up,” he continued. So I wandered through the interrogation rooms. Empty! No soul around. Back in the holding cell there were only two older prisoners, and neither of them looked like the young man that I’d seen picked off Harvard Avenue. The jailor confirmed the desk sergeant’s story. No prisoner had been brought in during the last hour. I went back to the desk to ask if there was any other place in the building where the threesome might be. “Well, you can look upstairs in the juvenile section,” the sergeant replied dismissively, “but you won’t find anything.” The offices and courtroom upstairs were all dark. I walked around in the dark corridor for awhile, bumping into walls, but found no one. I went downstairs and stood around the desk for fifteen minutes, thinking that my quarry might materialize from some hidden location. I wasn’t about to give up and go home like a good clergyman. I went outside. The Chevrolet was still parked in the driveway. I walked over to the garage behind the precinct station but there were only a couple of mechanics and officers standing around talking. As I walked back into the station out of the sub-zero cold, I noticed a doorway next to the stairs that I had missed when I first entered the building. On the door was a sign: “Task Force Unit — downstairs.” I opened the door and walked quietly down the darkened stairs. At the bottom of the stairs was another door, slightly ajar and leading to a room from which I heard voices. I walked through the open doorway and stood in a brightly lit room ringed with lockers. In the middle of the room was a desk. The two white men who I’d seen in the Chevrolet were sitting at the desk filling out their report. Their black prisoner sat sullenly against the wall in an old dark brown chair, head down.

“Yes, and what do you want?” one of the men asked in a hostile voice as I stepped closer into the room. “Are you the two men who took this man off the street?” I asked timidly. “Yah. What’s it to ya?” he said standing up. “Well,” I said, not backing down, “I saw you apprehend him and I didn’t like what I saw!” “Get your damn ass out of here...” (I shorten the verbal exchange which contained some sexually explicit language) he shouted, reaching a hand over to his shoulder holster. “If you want to make a complaint, go upstairs!” As the other white man came at me to physically remove me, I backed up, turned and exited the room. The black prisoner by this time had perked up considerably.

By now I was shaking with both fear and anger, not quite knowing which emotion had precedence. The desk sergeant turned to me with an “Oh, what now” look. “I want to file a complaint,” I said defiantly, which in any police station would make me an instant enemy, “against those two Task Force men downstairs.” “You’ll have to talk to the Watch Commander,” he replied. “Have a seat; this might take awhile. The Commander is out in the field.” After ten minutes the Task Force rogues (something in me can’t call them “officers”) came upstairs with their prisoner, stopped at the front desk, gave me a few “go to hell” glances, and took their prisoner back to the lockup. Up to this point everyone in the station house was white, except for the three black men now in the lockup. The Station Commander came in. “I hear you want to make a complaint,” he said, as he ushered me into his office behind the sergeant’s desk. The Station Commander was black, tall, powerfully built with hands twice the size of mine. He slowly explained that he had no jurisdiction over the Task Force cops who operated out of his precinct house. They were the para-military wing of the Chicago Police Department supervised from downtown. I told him my story. He countered, “The officers were responding to a reported robbery in the vicinity” (just where, he didn’t say). “But the man they grabbed didn’t run or resist. He was just walking down the street in plain sight” I countered, “and didn’t deserve the treatment he got. They didn’t find any stolen goods on him.” Our back and forth conversation went on, the Commander defending “His men” and I defending the young black citizen now under arrest. We were not getting anywhere in this strange racially juxtaposed conversation. He “explained” the stop and frisk rights that cops had. “You could be picked up anytime too,” he told me to illustrate his point. “On what grounds?” I asked. “Look, you’re suspicious. You’re white, and any whites who’re in the neighborhood after dark must be here for immoral purposes!” he continued. That was as far as I cared to go with our conversation, so I told him to forget the complaint and let me visit the prisoner instead.

He took me back to the lockup and had the jailor open the cell. The young black man didn’t know what to make of me, not really trusting me in the company of the Commander. We had no privacy and thus no conversation. The desk sergeant told me his bail would be $25 which I didn’t have on me. “In just another six hours he’ll be back out on the street,” he guessed. There wasn’t enough evidence to convict him of anything, and his case would probably be the first on the docket. “The only inconvenience this’ll cost him is a few hours in jail.” “What are you charging him with?” I asked. “Loitering,” was his reply. Right! At one a.m. in sub-zero temperatures who would be guilty of loitering anywhere? The Commander noticed the incredulous look on my face. “You’ve got to remember that this is a high crime neighborhood,” he said to justify police action. “I know,” I replied, “I live here.” I went back outside and got into my cold VW van and headed for home. It was 3 a.m. and Sue, my dear wife, was waiting up for me, pale with worry. “The Task Force cops must be hard up to fill their arrest quota,” I suggested. We went to bed and hugged each other tightly.

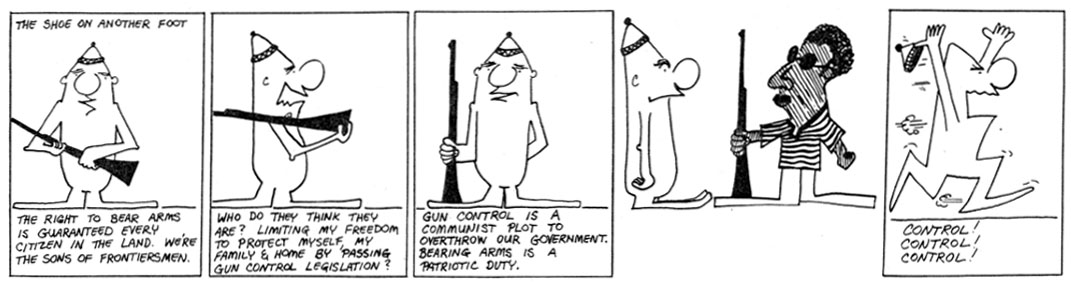

Two weeks later there was another police incident in the neighborhood, this time involving just the police, no one else. Sue was driving downtown to pick me up at Chicago Academy, and as she left with Philip and Joy aboard, she saw swarms of police at the corner of 65th and Yale, one block east of Harvard (we live on the Ivy League blocks). Later she heard on one of the black radio stations that a policeman had been shot by another policeman, a Task Force cop, while sitting in an unmarked car on a stakeout. The police must have suspected drug dealing in the apartment. Both cops were in plain clothes, both operated out of the Englewood station, but the shooter was Task Force and the victim was a regular detective; the shooter was white and the dead cop was black. The Task Force cop shot because he saw a gun on the car seat next to the victim, at least according to news reports. We’re not sure of any further details because nothing ever appeared in print. No further news reports were forthcoming. Two days later another swarm of police was at the corner of 65th & Yale reenacting the scene. The word on the street was that the police were out to disarm the ghetto and confiscate all the weapons they could. We do need a national program to get guns off the streets, also in the suburbs.

My attitude toward police had turned decided negative. I could understand why ghetto residents were reluctant to report things to the police, which would likely invite trouble. The police were called only as a last resort, and then never fully trusted. Police who worked in Englewood didn’t live in Englewood, since at the time 95% of them were white. Just a month previous I had gotten a ticket for making an illegal U-turn at an intersection up on the north-side after a family gathering. I was pulled over and issued a ticket. Four year old Philip became incensed with the cop, and as the cop was busy writing out the ticket I was busy restraining my son who thought an injustice was being perpetrated. I explained that I was wrong and the officer was right. I’m sure Philip had observed my attitude toward police, which wasn’t good. The police in Englewood were in a difficult position: the crime rate was high, the “hood” was dangerous, and people were reluctant to trust them (the white anti-war protesters even called them “pigs”) and they had the responsibility for keeping the peace. It was no wonder that the police had their own code of ethics (much like the teen gangs) and grouped in their own subculture. They too were driven by the survival instinct, which on plenty of occasions was inflamed by racism. The role of black cops also was difficult, for they were under pressure to show their white peers that they could control their own people. It is unfortunate that the acronym “cop” (constable on patrol) is no longer true: today cops sit in squad cars and don’t walk a beat anymore. People don’t get to know them and they don’t get to know the neighborhood. Chicago cops are outsiders, thought of as an occupying army.

In February I received an invitation to fly to Cleveland for a job interview. My Seminary classmate, Dick Sering, and the Cleveland Metro Ministry which he led were looking for a community organizer to work in a poor white section of Cleveland. It was an interesting day. I met Joel Kischel once again. He drove me to the airport that night and wanted to talk and share the faith. I almost missed my flight, the last one that night back to Chicago. I had to sprint through the airport, run down the gangway, pound on the closed door of the plane, and an alert flight attendant opened the door for me. I didn’t have to sleep in the terminal that night. I didn’t completely catch my breath until the flight was landing at O’Hare in Chicago and by that time I was certain of one thing: I’m not constituted to be a community organizer. I can barely keep Our Redeemer congregation organized.

Next: The Chicago Memoirs of 1971 (Part Two)

|