|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1971 (Part Two)

“Our VW bus was a real utility wagon. Not only could it haul plywood, plasterboard, and other construction material needed for the repair and maintenance of Our Redeemer, but it could also haul people. In the day before mandatory seat belts, we once hauled 22 children on a short trip to a Lake Michigan beach during a summer program.”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

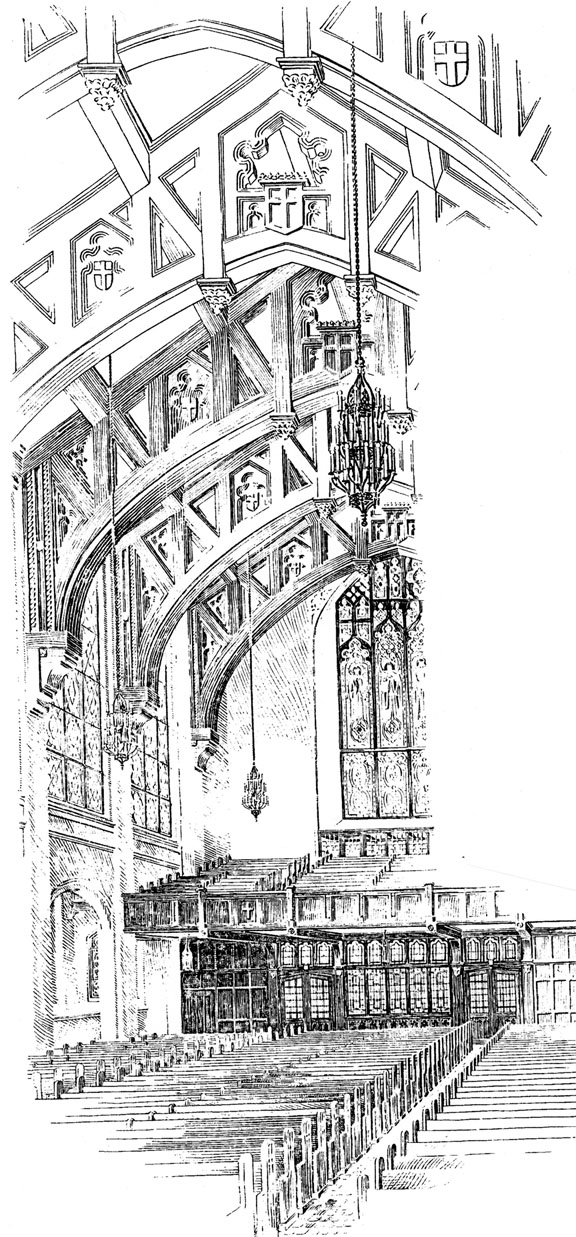

We decided to celebrate Our Redeemer’s 70th anniversary as a congregation in a big way, partially because we weren’t certain it or anyone now present would be around to celebrate the 75th, given the fragile health of the congregation. Our Redeemer, like the people in its community, was fighting for survival, an on-going daily process that after a while became so routine that we actually became used to insecurity. We printed posters, mailed out invitations to former members, and invited Paul Schuessler to preach. On the morning of Sunday, February 21 there were 63 people in church; for the afternoon anniversary celebration there were 255. Paul Schuessler preached about “Paradoxes of Power”: that his grandfather, “a tall slim man riding his bicycle down 63rd Street,” actually started a congregation 70 years earlier that eventually built the “Cathedral of Gospel Art” — from such humble beginnings to such a magnificent structure. To me the paradox was that with such a small worshipping congregation we were able to help and serve so many poor people. Be that as it may, we enjoyed Paul’s personable presence, many warm “homecomings,” a surge of positive thinking about the church’s future, and a good plate collection. I drove Paul out to O’Hare for his flight back to St. Paul. We got a late start, thanks in part to a couple martinis, and he ended up running down the O’Hare corridors, pleading with a flight attendant to let him board, an exact repeat of my flight home from Cleveland.

I sent my Mission:Life lessons to St. Louis only 2/3rds complete, in protest over the devastating, heavy handed editing job which mutilated the previous lessons Bill Schmidt and I had submitted. About 95% of our material ended up in the circular file since it supposedly contained “too much social gospel.” Perhaps we were guilty of using too much urban slang addressing too many social issues, and yet our “street talk” resonated with the kids we used to test our material. What was going on in St. Louis at the time was the Preus purge of Mission:Life and its staff at Concordia Publishing House, the first casualty in what would soon become a church-wide disaster. The repudiation of the “Mission Affirmations” affirmed by the 1965 Synod Convention, which lent so much support to urban ministry, campus ministry, and the work of institutional chaplains, had begun, and a brief creative era in the denomination came to a disastrous end. The irony was that the unfinished eighth grade material which I submitted was used in its entirety, a fact that later made me ashamed of the heavy accusations which I made in my accompanying letter. I was at my judgmental worst; my editors weren’t the enemy.

Our own personal survival was supported by “the Group” — eight couples who regularly met together for socializing, mutual support and for some venting at “sensitivity sessions”. Four of the couples were involved in urban ministry: the Beckers, Hrbeks, Theisses and Nickels; and four other couples were struggling in the academic setting of Concordia College, River Forest where their jobs were on the line due to a reactionary college president, Paul Zimmerman. One participant in the group was a trained clinical psychologist, so we could air our frustrations in the context of professional help. When you live and work in the ghetto you absorb some of the mental struggles people have: how can you measure success when the deteriorating environment suggests you’re a loser? How can you process subliminal anger in a constructive manner? How can you break out of a “confinement” which limits choice, mobility, security, and physical health? Is there an antidote to the feelings of abandonment — this nagging realization that as white people working in the black community we don’t really belong anywhere and are greeted with some suspicion by both blacks and whites, having white skin but a black heart? Our situation put huge stress upon couples. The difference between our circumstances and that of the black residents of the neighborhood is that we have the option to leave — the escape route is always there, so why are we complaining? Isn’t this what we signed up for?

In Chicago at the time there were also many white families on welfare, so it’s a mistake to assume “welfare” is a black ghetto problem. EWRO had white members and Our Redeemer had white members on welfare. When EWRO signed up people, they were also always invited to attend church at Our Redeemer and join the congregation. Charlie was one of these people, an alcoholic married to a black woman; they had two beautiful children who were forever trying to cope with two alcoholic parents who also had serious mental problems. I spent untold hours with Charlie, counseling, sobering him up, feeding him, and gave him odd jobs with pay when sober, so that he wouldn’t “go downtown” and sell his blood to the Red Cross for booze money. He had hepatitis, but this was before the Red Cross checked the blood supply. Charlie could never stay on the wagon, and I often found his bottles hidden in the furnace room. Anthony Tanas and his wife were another white couple who became members of Our Redeemer. Tony had a long history of psychiatric problems, forever nervous and sweating; but his wife, thin and frail, stayed faithfully by his side. They lived in a roach infested apartment above a pool hall on 63rd Street. Tony was in and out of Manteno State Hospital. His body was covered with tattoos (long before tattooing became accepted and popular) and both Tony and his wife came to my adult membership class and became members of the “body of Christ.” Tony had a spider tattooed on the top of his bald head, more than a little visually disconcerting when he came kneeling at the communion rail. The Tanas’ defenselessness made them a target for beatings and robbery; fear kept them in their apartment after dark, and after one severe beating they relocated to the north side of Chicago. Donald Krager was another “case” — my contact with him spanned two years. He was referred to me by Bill Schmidt in Detroit (thanks, Bill) and was a royal pain in the neck. He too had a history of psychiatric problems and could hold a job for only two weeks before conflict with other employees (usually as a waiter at downtown hotels) would get him fired. He travelled all over the USA, usually by bus, looking for work. I’d receive long distance phone calls from Lutheran pastors asking if I’d vouch for Krager and if he was “truly needy.” He refused to face the mental problems that made him truly needy. But he needed more than bus fare — he needed human contact. Finally I had to stop vouching for him, and he took to impersonating me, making a local phone pretending it was me calling long distance to some Lutheran pastor, asking him to “meet a Donald Krager at the bus station and loan him some money, and that I’d guarantee repayment.”

Our VW bus was a real utility wagon. Not only could it haul plywood, plasterboard, and other construction material needed for the repair and maintenance of Our Redeemer, but it could also haul people. In the day before mandatory seat belts, we once hauled 22 children on a short trip to a Lake Michigan beach during a summer program. We also managed to cram 18 teenagers into the bus for a trip out to Concordia College for a ‘free gym’ basketball game on Sunday afternoon. We also managed to shoe-horn 13 children and five adults into the van to attend a Saturday morning play at the Children’s Theatre at Concordia.

Our Redeemer was “home” to many kids, but at the same time it was a “mark.” Early in April we received a gift of about 100 blankets from Trinity Lutheran Church in Roselle, IL. We stored the new blankets in the converted coal room in the church basement, thinking that was the most secure place in the building, expecting to give the blankets to families burned out of their apartments. The blankets were delivered in the daytime, and someone’s observant eyes must have gotten an idea. A few days later we discovered that someone, obviously small, had squeezed through the outside window of the ladies washroom in the parish hall basement, a feat which required the forcible removal of the metal sheeting I’d bolted over that window after the last break-in. The building generally showed the marks of the ongoing contest between the Our Redeemer security officer (me) and some potential thief. The furnace room door, made of heavy metal plate, had been pried loose thanks to a vulnerable oak door frame. The building code required that the door had to be unlocked “during business hours” but we made sure every night that it was locked for the night. One morning we saw the busted door frame and knew that the 100 blankets would be missing. Thanks to the continual need to “boast” to bolster reputations out on the street, there were actually few secrets that we couldn’t track down. Otis‘ ear was especially tuned to the street talk, and he found out that a group of boys had broken into and entered the building and furnace room, removed the blankets, and then went door to door in the surrounding tenements selling blankets for 50 cents apiece. After my anger and disappointment subsided, I decided that this was probably a pretty good distribution program after all: the kids got to share $50 and the people who purchased the blankets got a huge bargain. We probably couldn’t have done any better with our piecemeal distribution. What was affirming was that these kids identified Our Redeemer as “my church” whether they worshipped with us or not. It was a church with resources to be distributed; our house is your house. But this identification didn’t prevent break-ins. There was a Saturday night break-in at the church which I discovered early Sunday morning when I noticed the broken door jam to the sacristy, smelled the burnt oak paneling, and pushed in the askew door now missing a hinge. This thief had forced his way into the furnace room, taken some of our tools — a power drill, crowbar and propane torch — and went to work on the sacristy door upstairs, because he knew that in the sacristy there was a big safe. He used my blue Advent stole to muffle the sounds of the drill as he went to work on the safe. It became a “hole-y stole” as he drilled through the fabric to attack the overturned safe. He never “cracked” it. In fact, we had long ago lost the combination and nothing of value was in it. Will McCluster with his ear tuned to street talk, indicated to me who the culprit was. I confronted the young man and pointed out his stupidity. First, don’t knock over a church on Saturday night — the offering hasn’t yet been collected. Second, don’t assume anything of value is in an old safe just because it looks big and formidable. Third, go to school and get an education so that you can move up from blue collar crime to white collar crime, if criminality is your career choice. Blue collar crime is punished severely (usually) while white collar crime is excused with a little slap on the wrist. I don’t know if he got wise.

Our Redeemer indeed provided a beautiful interior space in which to worship. Especially on Easter, as if resurrection hope needed light from above, the sun shone through the east wall Te Deum window and diffused multi-colored light throughout the nave. This Easter 126 people gathered in church, and the numbers held out hope that we might make a comeback. The Wolters, a white suburban family, transferred their membership to Our Redeemer, in this one instance fulfilling Luther Schuessler’s dream of the Dan Ryan Expressway bringing back hundreds of departed members, making “the rough places smooth and the crooked places straight,” returning from “the suburban captivity of the church”. The Wolters were surprised how eagerly they were welcomed, not fully realizing what they symbolized.

On Wednesday, April 14, the day after Sue’s birthday, Daniel Kipp Nickel was born, all 10 lbs. 15 oz. of him. Sue had a difficult time with his birth and lost a lot of blood. She needed transfusions (unfortunately coming from the unchecked blood supply from which she acquired hepatitis). Sue was still in the hospital on the 17th when Philip had his first birthday party with the Theiss kids and kids from Ancona in attendance, all five year olds. Thanks to help from Darcy Marxhausen, I made it through the party with my sanity intact. The addition of another member to our family and our vulnerable housing location made us re-examine the possibility of looking for a home to buy “out south” (never a precise location because ‘flight from blight‘ was ongoing and its boundaries always shifting). We even made an appointment with a real estate agent and drove around the Beverly neighborhood looking at homes for sale, always cheaper on the boundary between the black and white communities. We abandoned our search for two reasons: first, the congregation couldn’t afford a “housing allowance” in addition to my mission board scale salary, and secondly, what local credibility I had was because I lived in the neighborhood, even though three blocks away from the church few people knew who I was.

The first Sunday in May I invited Jim Hawthorne to preach. Jim was a former black Baptist minister in Robbins, IL who was now a student at LSTC. He was due for a year of internship the coming September, and I thought it a good idea to investigate if he’d be interested in serving his “vicarage” at Our Redeemer provided we could get approval from LSTC and the English District. While that didn’t happen, Jim actually did serve Our Redeemer after we moved to Champaign in 1972. On this first Sunday in May, Jim’s wife, Lorraine, sang a solo, which endeared both of them with the people of Our Redeemer.

On Rogate Sunday (we were still using the old liturgical calendar names for the Sundays based on the first Latin words from the introit, a practice long ago abandoned that needs to be revived) we held our second annual “Earth Day” service, worshipping first, blessing tools, seeds and people, and then converged on the parking lot, vacant lots, and the street in front of the church in a valiant attempt to clean away the debris of a disintegrating neighborhood. A total of 58 people pitched in. We were joined by some neighborhood children who figured one of the vacant lots would make a nice baseball diamond, and they helped clean it up. The building strippers provided a lot of junk to clean up — the stuff that couldn’t be converted to cash at the junk yard. Sober’s building wasn’t the only one hit. One recent afternoon in broad daylight a pick-up truck backed up to where the front, beautiful French doors and windows used to be in the building directly across the street from the parsonage, and they started heaving the heavy cast iron radiators out the window into the pick-up bed. The clanging noise drew Otis and myself on the run. When the scavengers saw us coming, they jumped out the window, got into the pick-up and sped off down Harvard Avenue. Otis got the license number, called the police, and then notified the woman who owned the building. Indifference marked the demise of the neighborhood, and no one was arrested. Otis and I found ourselves in the curious role of policing abandoned buildings, and our Earth Day work barely made a dent in the rubble. We felt that the brazen daylight stripping of buildings was indecent, a “Samsonesque” disdain for once substantial architecture, a social anarchy that was destroying habitat without considering the effects of such destruction. It was opportunistic robbery pure and simple and no one cared. Owners were content to pick up their insurance checks, the police couldn’t be bothered, and the neighborhood turned into a wasteland with inhabitants mindlessly contributing to the destruction for a few pennies profit at the junk yard. It takes huge effort to build, but not much energy to tear down.

The Our Redeemer Altar Guild held their golden anniversary at a restaurant in the Beverly Hills neighborhood out on 115th Street. The Guild had long survived the demise of the Ladies Aid because it welcomed new black church members right from the start. Today it was still going strong despite the increased age of its members, thanks to the tireless labor of Marie Sternberger. Marie and her husband (now deceased) were the first couple to be married in the “Cathedral of Gospel Art” after it was dedicated in 1923. Marie always boasted that she’d be the last to leave Our Redeemer, and in October 1973 she kept that promise as the building was sold by the English District and its doors were closed for the last time.

The building was suffering from “architectural arteriosclerosis” and its sump pump was a case in point. The float switch failed to work and the basement (one bathroom, the furnace room and the crawl spaces under the aisles) flooded. Jay Frost, our electrical troubleshooter came to the rescue. Jay, one of our faithful white members, was now in business for himself running a shoe store, but he had worked as an electrician and had contacts with other workmen — plumbers, pipe fitters, metal workers — a ready source of referral. Jay introduced me to the cavernous crawl spaces that contained the heating pipes, and we spent time and energy under the church, trying to find pipe leaks, poisoning rats, installing gas pipe, and thawing water pipes in winter. Second only to the the real claustrophobic nightmare of the crawl space, my worst imaginary nightmare was the boiler directly under the chancel exploding while I stood above it on a Sunday morning. That really would be “high church.” It never happened, thanks in great part to Jay’s skills.

To make matters worse, this spring the city tree crews were at work. Usually they’d be called upon to remove dead or fallen trees or to clear power and telephone lines. But one fine spring day we found them coming toward us down our one-way street, removing all the vital, living trees along Harvard Ave. between sidewalk and street. It seemed like we were being forced to deal with one atrocity after another. Otis and I inquired from the white foreman why they were removing such a healthy tree from the parkway. “Orders,” was the curt reply. Otis threatened to report their activity to Mike Royko, acidic newspaper columnist for the Daily News who was adept at taking on city hall and the crew quickly made their last cuts, ran branches through their chopper, swept up their sawdust and took off. Our question of “why such orders” went unanswered, but Otis was of the opinion that they were taking down the trees so that authorities could have clear over-head helicopter surveillance. I thought that rather farfetched until a few nights later, while working at my drawing board in the attic “art room” drawing a cartoon for George Hrbek’s “Incite” Lutheran underground newspaper, I heard the whirling blades of a chopper. Looking out the small attic front window, I saw a huge spotlight flooding the street in front of the church building coming from the copter overhead. I called for Sue to come up the stairs to the attic and observe the scene with me. We were indeed under surveillance from above, and it wasn’t a comforting presence. In the next month the chopper would return almost nightly.

One of our needs was to find accurate sources of information which weren’t forthcoming from the black “Daily Defender” or most other newspapers. One troubling but accurate source of news was “Muhammed Speaks,” the Black Muslim newspaper to which Otis subscribed. The paper, named for Elijah Muhammed, was troubling for me because of its inflamed rhetoric and often anti-christian slant (“christianity is the slave owner’s religion”), but its news stories about community action on the south-side were accurate. There were also international stories detailing troubling effects of US “imperialism” on African nations. The conduct of the Vietnam war, “white America’s war,” was also a focus. Muhammed Ali was their celebrity hero because of his refusal to serve in the military. I especially remember one article complete with photos detailing obsolete WWII Army prisoner-of-war camps being readied as detention centers in time of civil unrest. “Muhammed Speaks” had no trouble visualizing who those camps were being prepared for. A dozen years later after Watergate journalists uncovered records of Attorney General John Mitchell’s plans, confirming the accuracy of “Muhammed Speaks’” investigative journalism.

Some of the teens who hung out around our “community center” (as we now called the parish hall) were giving Otis a lot of trouble. So Otis promised them the sponsorship of their rag-tag baseball team by the community center if they would get it together and enter the Chicago Park District League at Washington Park. They came to call their team “the Redeemer Royals,” a name which really affirmed Otis and our staff. Many of the team members had at one time or another broken into our building but now picked the church name for their baseball identity. Some of them started newspaper routes to earn money to buy equipment! It was unheard of for there to be a newspaper route in the ghetto due to the problem of collecting money. These “delivery boys” didn’t have that problem, for they know who lived where. You better believe they could collect.

Behind the church and sacristy were two four story tenements. The second floor occupant had a grill on his back porch on which he slow roasted ribs almost every Sunday morning during the summer. The aroma came through my open sacristy window, reminding me to keep the sermon short so that I, too, could get my grill going for a proper Sunday noon dinner. The secret must have been in the sauce, because my ribs never tasted as good as his smelled. He wasn’t a church-goin’ man, or I might have traded him his recipe for a little pastoral grace.

I was elected to be the alternate delegate to the Milwaukee Convention of the LCMS, and by default later attended the summer convention as a voting delegate. My experience was a distant parallel to Martin Luther’s trip to Rome, becoming disenchanted with the traditions of the church and the on-going right wing take over of its leadership. The trumped up charges of heresy were a smokescreen for the power take-over. One of my Mission:Life lessons was accused of heresy, written up in a memorial and addressed in a pre-convention hearing; the fortunate thing was that my accuser had misquoted scripture and had to back down. The real casualty of all this maneuvering was the mission of the church. I came away with a new understanding: you can always detect the presence of self-righteousness by the necessary banishment of a scapegoat. The LCMS in convention had to prove its self-righteousness, and did so out of frustration by voting the Walther League, the youth program of the church, out of existence. I spent a lot of time outside the convention hall comforting the young Walther Leaguers who didn’t know what hit them or why they were singled out for judgment. Those who were “over 30” didn’t trust those who were under 30, as the League had started to promote a “youth led movement” with peace protests starting to be voiced. Forty years later the LCMS has all but abandoned campus ministry because there are so few young people affiliated anymore with the church.

Next: The Chicago Memoirs of 1971 (Part Three)

|