|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1968 (Part Six)

“The irony about the ’60s was that it started out in the optimistic throes of Camelot and ended in the nihilistic swamp of Vietnam. The ’60s was both a very creative decade and also one in which the “free love” movement went off the road and crashed.”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

Otis Flynn was hired by the Board of Social Ministry to replace Barbara, and he started working for us in July. Otis would prove to be even more effective than Barbara and had the welfare of the Lutheran Church at heart. I would tend to the Sunday congregation and Otis would tend to the weekday congregation. The Sunday congregation provided and channeled resources to the weekday congregation and the weekday congregation lent the Sunday congregation legitimacy. It was the start of a good working relationship. We started an eight-week summer program with the multitude of children who used our parking lot as their playground. It was a busy summer.

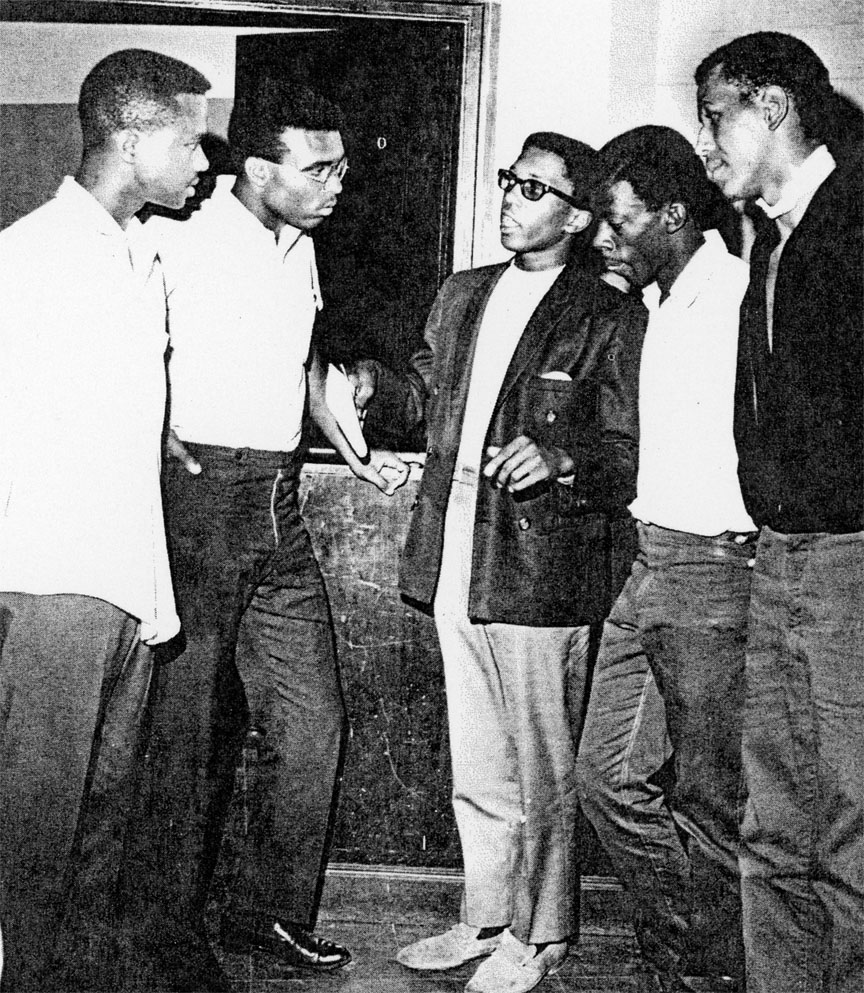

Otis Flynn, second from left, speaks with Sylvester Philips, center, about the Parker High School walkout.

Officials in high places suddenly had money to spend to try to “keep it cool.” As their poster said, “Only you can prevent ghetto fires!” Move over Smokey. City programs seemed to employ every black teen they could find.

In the midst of the chaos of 1968, beautiful little Joy Kristin Nickel was born on July 10 at 5:15 p.m. at Wesley Memorial Hospital downtown. Joy was healthy and fragile despite her 8 pounds, giving us a new life to care for and love. Her name was our existential shout to the world. We brought her home to the heat and noise of the parking lot, a child of the ghetto. By the time she was a month old, we travelled to Readlyn, Iowa, for John and Kathy Hirsch’s wedding, where I did the preaching. John had been an intern staff member at Riverside Church in Detroit who subsequently studied for the ministry and was soon to be ordained. He was a good friend.

Pastor Bertwin Frey was president of the English District and very supportive of urban ministry and Our Redeemer in particular. His address to the convention this summer was bold and forthright:

“Our Savior didn’t promise us easy going, and we won’t have it easy if we are faithful to Him who went about doing good and follow in the train of those who ‘disturbed cities’ and ‘turned the world upside down.’ The ‘status quoers’ will squeal and howl. The traditionalists will raise their eyebrows. The peace of mind cultists will resent your agitation ... withhold funds ... claim orthodoxy ... change the truth of God into a lie. ... But to the Christian who would preach the Gospel of Christ’s love and reach out with the hand of love wherever and whenever he can, they are only the signals for a cross-bearing ministry that may leave its scars. ... God will not look you over for medals, degrees, or diplomas, but for scars!”

I had to leave the convention early to return home for the funeral of Mrs. Martha Jabusch, elderly and faithful member of Our Redeemer. She was the grandmother of Fr. Richard Jabusch, Roman Catholic priest and author of some hymns we were using in our “Redbook,” our duplicated supplement to The Lutheran Hymnal. “The King of Glory Comes” based on an Israeli folk tune was a favorite. He officiated at the service with me at Our Redeemer by my invitation, an “ecclesiastic crime” in Missouri–Synod circles but intensely meaningful both to me and to Martha’s family, with its Lutheran and Roman Catholic “wings.” I always remember that Pauline passage: “Where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom!” In such freedom we celebrated Martha’s long life, with our joy placed in Christ’s promise of eternal life.

Joy Kristin Nickel arrived July 10, 1968 at Wesley Memorial Hospital.

The first two weeks in September Joy became a seasoned camper when we loaded up our VW bus (the first of many westward camping trips) and drove nonstop to Colorado for our first look at the Rocky Mountains. Uncle Jim and Beth Grams were along for the ride. The VW bus, outfitted with a plywood platform in place of the middle seat, was an excellent camping vehicle, but seriously under-powered for the mountains. The aspen trees and cool mountain streams (where I caught my first trout) soothed our tired souls. This contrast made our return drive back to Chicago difficult in the extreme.

It had been a difficult summer. Senator Robert Kennedy was shot and killed, further reminding the nation of its vulnerability to violence. Congress discussed gun control legislation, but the NRA lobbied it to a standstill. The arms race now was now at full tilt in two directions: promoted by the military-industrial complex through excessive fear of communism, and by your local gun shop through excessive fear of race. The Democratic National Convention managed to reintroduce rioting to Chicago and drew a determined backlash from “Hiz honor, da May’r” Richard J. Daley, who called out his troops in blue, eager to bust heads at Balboa and Michigan Boulevard — white heads this time. It was “deja vu all over again.” Instead of Black Panthers we now had the Weathermen, and after that came the extended show trial of the “Chicago Seven.”

The tension in the city thickened, with demonstrations about war and race now competing for press coverage. Rumor had it that the anti-war radicals planned to poison the city’s drinking supply, to which some responded that they would do it with hashish so the entire city would get high, and finally make love, not war. The irony about the ’60s was that it started out in the optimistic throes of Camelot and ended in the nihilistic swamp of Vietnam. The ’60s was both a very creative decade and also one in which the “free love” movement went off the road and crashed. Drugs were on the market (it became popular to trip out with LSD), even though the drug of choice in Englewood remained Ripple Wine. I often had the privilege of sweeping up the broken glass from busted wine bottles thrown into the church parking lot, but seldom did I find a syringe.

Up until now I wore my clerical collar every day. It was an identifying symbol, cutting through all sorts of miscalculations, indicating my role and purpose in the ghetto. Though white, I was not employed by the police, insurance companies, or some other government agency. A collar and a beard were sort of a badge of safe passage wherever I went but that was changing drastically. Thanks to protest movements, now if you had a collar and a beard, you were under suspicion and likely to become an “anti-establishment” police target.

There were continual changes happening in our parish. Dr. Gieschen took a leave of absence, and played a benefit farewell organ recital despite having his knee in a cast. At his leave-taking the church choir disbanded after many years of faithful service. Wendell Clark, a student of Tom’s at Concordia, was hired to be Tom’s replacement. Wendell grew up in the Baptist Church in Kansas City, became attracted to the Lutheran Church through his parochial schooling, and brought his considerable musical talents and Baptist hymn style with him to River Forest and then to Englewood. On the fourth Sunday after Trinity there were 108 people attending church, a high point for a summer month and certainly a vast improvement on our post-riot attendance. In Washington, D.C., the McClellan investigating committee was busy trying to discredit the Rev. John Fry, rebel white pastor in Woodlawn who was working with the Blackstone Rangers gang, and investigating The Woodlawn Organization (TWO), a Saul Alinsky-designed community organization famous for its opposition to the Daley Democratic machine.

In October we marked the 45th anniversary of the dedication of the present church building (though the congregation long preceded it at another nearby location). With Otis in the lead, we again set up a tutoring program with the help of students from Concordia Teachers College in River Forest. Welcome back! Church attendance was averaging in the mid-80s. Wendell continued the teen choir which Tom Gieschen had started, and they began to introduce some folk tunes and music with a beat. It was part of “the great cultural revolution” at Our Redeemer — my intentionally inflated and tongue-in-cheek term for what happened: White members thought change was happening too fast and black members thought change was happening too slow. My stance was that of a “moderately conservative radical” — trying to conserve what truly grew deep (with roots like the radish) without self-destructive extremes. Black Methodist Pastor John Porter, together with Pastor Norm Theiss from our neighboring Northern Illinois District parish, St. Stephens, began the Englewood School of Human Dignity which met at Our Redeemer, teaching black history to anyone who elected to attend, black and white. The focus was black history, cultural symbols and images, and the Swahili language.

Banners arrived

Their bright colors and shapes transformed the dark, quiet nave. Not everyone was happy, but the children led the way to a worship of celebration.

We started introducing banners in the church nave, disliked by those who assumed that because God was changeless His “house” shouldn’t change either. But bright colors of celebration were at home in the black culture and they have a long history in Christian art. Liturgical renewal also hit the Sunday School. “Wade in the water” became “Washed in the water” thanks to new wording by Bill Schmidt, friend and Lutheran pastor in Detroit with whom I often collaborated. “See us people living free, God’s love flows through the water, black and proud in this country, God’s love flows through the water” and refrain, “Wade in the water, children ...” Our young children led the way into the worship style of celebration.

Will McCluster, our elderly black janitor, was wearing out. To help him, I spent time making repairs and became well acquainted with the building from the roof, six stories above the street, to the cavernous crawl space under the side aisles — an underground “U” shaped tunnel carrying heating pipes from the furnace room. My claustrophobia, triggered by forays into this undercroft, began to show up regularly in nightmares. So I drew a cartoon in our parish newsletter, “Like-it-is”, with Will, Otis, and me doing some pipe fitting in the undercroft. Building security was also a constant problem. We could see strangers on the parish hall roof from the parsonage bedroom. “Look,” Sue nudged me one night — there in the moonlight was a “visitor” looking for entrance through the skylight over the three-story stairwell. “Not to worry,” I told her; he has a long way to go down. But access was gained through the old coal chute, through a window in the “dugout”, through broken doors and windows. No sooner did we patch one hole than the kids found another. There wasn’t much inside that could be hocked, except office equipment in Otis’ office, so we doubled security inside the building as well.

That fall I was also working long-distance with Bill Schmidt to get our colorful flip charts, “Say and Do Love” ready for publication by Concordia Publishing House in St. Louis. We kept phone lines between Detroit and Chicago busy. We later collaborated on other educational projects — Bill Schmidt with his songs and I with my art; we both did some writing.

Our evening Advent services were well-attended, in part because I offered my VW bus for taxi service on the homeward journey. We worshipped around the side altar at the rear of the church. I used the overhead projector and made collage transparencies to preach visual, participatory sermons on Advent themes. The first week in December Hilmar Sieving had a growth on his arm removed at Woodlawn Hospital. It was malignant. On the third Sunday in Advent the teen choir sang the “Sanctus” from Fr. Peter Scholtes’ new liturgy, the “Missa Bossa Nova.” They even used drums. Otis was working hard to increase the capacity of our food pantry and started gathering welfare recipients together which would eventually lead to the formation of the Englewood Welfare Rights Organization.

Next: The Chicago Memoirs of 1969

|