|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1968 (Part Two)

“[The usher’s report]: There is no heat in the building and everyone is cold! I already had on my white surplice over my black cassock, but went downstairs to the furnace room in full regalia and began shoveling coal. By the time Tom Gieschen’s extra-long prelude ended, the pipes were starting to heat up, banging away with some echo effect in the large nave.”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

The coal furnace was regularly breaking down. The auger jammed, its motor burned out, and it often had to be stoked by hand. Will McCluster, our janitor who lived just a block down the street, was usually adept at coaxing it along. On a Sunday morning during the winter the heating pipes were not banging when I arrived to set up for the morning service. I worried that we were about to have another furnace malfunction, but became involved with setting up for the service. About ten minutes before worship was to start, Art Wuerffel, one of our outspoken elderly members came back to the sacristy with the word: “There is no heat in the building and everyone is cold!” I already had on my white surplice over my black cassock, but went downstairs to the furnace room in full regalia and began shoveling coal. By the time Tom Gieschen’s extra long prelude ended, the pipes were starting to heat up, banging away with some echo effect in the large nave. That normally disruptive sound comforted the shivering congregation — heat was on its way. The pastor was the furnace man of last resort.

The huge space within the sanctuary of Our Redeemer had become an impediment to worship now that our Sunday attendance was dwindling. How could we stay in touch with each other, wrapped together within the “tether of the Spirit?” Is it possible to invite Lutherans to sit together? To touch? To share the peace? Our little greeting, “The love of Christ unites us,” was a beginning. I had tried chanting a strictly liturgical service using Page 15 from The Lutheran Hymnal, since the wonderful organ played magnificently by Tom Gieschen (a music professor from Concordia Teachers College in River Forest, who was deeply committed to the ministry of Our Redeemer) resonated so mightily within the walls and invited “high liturgy.” Tom was also adept at repairing and tuning the organ, saving the congregation much money. But the traditional Page 15 service was not easy for our black members to use. Liturgy is, after all, only a tool to use in our praise of God, and it should fit our circumstance; it should be in our “soul language” and not from some other place and time.

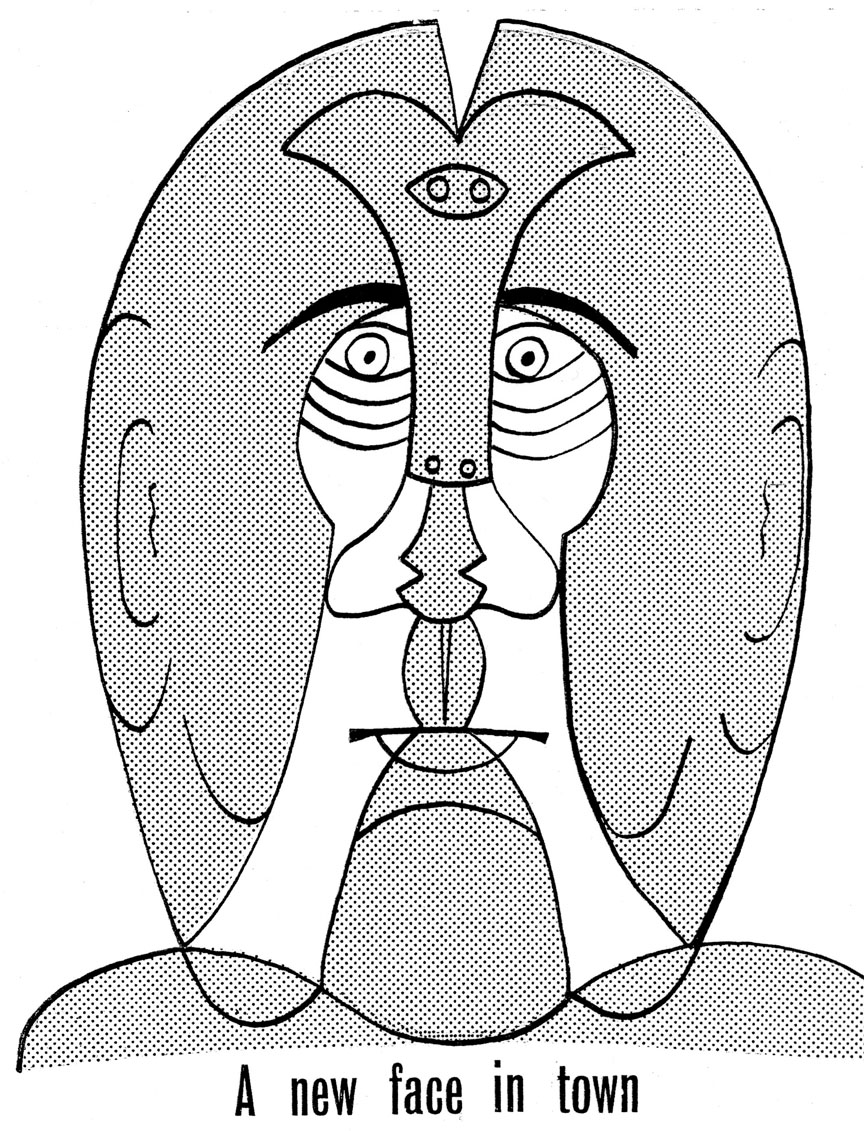

A new face in Town

Richard J. Daley — “da Mare” — superimposed on Chicago’s iconic new public sculpture by Pablo Picasso.

We kept to a definite liturgical style which satisfied most of our white members, but the music and spoken vocabulary were beginning to change. Our Redeemer was an English District parish. The English District came into existence at the start of the 20th century, heralding the use of English at a time when most Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod parishes still used German. The English District was also non-geographic, with parishes spread over the whole country, most often in urban areas. So there was precedent for experimentation with language and worship styles.

The huge Cor-Ten steel “Chicago Picasso” sculpture had been installed at the Civic Center in the summer of 1967. Mike Royko, columnist for the Sun Times and supreme Mayor Daley critic, began running a number of columns asking readers, “What is it?” It prompted me to draw a cartoon, “A New Face in Town,” which superimposed “da Mayr”’s corpulent face over the Picasso outline. I never sent it to Royko but kept it on file. I found this clash between Royko and Daley to be humorous: Royko playing the cultural philistine and Daley putting on social airs of refinement with the well healed art crowd at the museum. This was Chicago at its cultural climax.

Early in 1968 we walled off an office room in the large parish hall to be used by our new social ministry program — our community outreach. Thanks to a special subsidy grant from the English District we interviewed and hired Barbara O’Banion, a capable, articulate, young black woman and she began work toward the end of February. Barbara didn’t have a Lutheran background but was eager to fit in and make an impact, and she had many ideas and a lot of energy. She was also militant and had friends in those circles. She made contact with some high school students from Parker High School located about six blocks south of Our Redeemer. These students were willing to help teach in our Wednesday evening tutoring program in exchange for being able to use the “dugout” (a basement room beneath the parish hall) for the meetings of their Afro-American History Club. The white female principal of Parker had refused to let any “racist group” meet in her school and refused to let the group have the faculty sponsor of their choice.

Some of Barbara’s militant friends started hanging around on Wednesday nights and soon made the demand that we get rid of the white college students from Concordia Teachers College in River Forest who drove down to the South Side on Wednesday evenings to lend a hand. “Whites can’t teach blacks what they need to be aware of,” Barbara’s friends told me. “White tutors just complicate the problem of black identity because the children have no positive black image to identify with.” We made an uneasy truce. It wasn’t only the college students who were on the firing line, but the white pastor was implicated as well. My relationship with Barbara grew tense: Her black friends were not helping with the tutoring project, just rappin’ — and talk is cheap. I explained the situation to the Concordia students, and at the end of their academic quarter they no longer came to Our Redeemer. The high school students from Parker were doing a good job.

During Lent I preached a series of dialogue sermons with Hilmar Sieving. It was an enjoyable experience, and the first time any layman delivered a sermon at Our Redeemer. Members were still willing to drive into the neighborhood for evening services, a willingness that was soon to change.

Next: The Chicago Memoirs of 1968 (Part Three)

|