|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1968 (Part Four)

“Neighborhood children ran in and out, happy to be at the banquet. It was a family affair, successful because most of the people were finally given an opportunity to affirm each other, black and white, rather than have their choices and tastes dictated by outside forces. It was good to express unity rather than be the victims of separating forces. But unfortunately this was only a brief interlude.”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

So just where did we fit in? Could I continue to function in a pastoral role? Sue and I were white people in a black ghetto who were partisan to the black cause and therefore aliens to the white community where we didn’t live and where we were met with distrust. We were a minority and held a minority viewpoint, and that realization in itself confronted us with a great but steep learning curve. The upshot was that from this vantage point we could look through all posturing of superiority and see it for what it was: Often driven by fear, it sought to dominate and control and could do much damage. But it was a “paper tiger.”

I resolved to be unapologetic about my calling. The Lord saw fit to put me in Englewood at Our Redeemer at this time for His purposes, inscrutable as they were. I had to earn respect to be the “blue eyed soul brother” by paying my dues. The tension was between being paternalistic and permissive on the one hand and insensitive and distrustful on the other. I was the easiest “touch” on the block, but I also knew how not to get “white-mailed” by guilt. I could see through the stories and call a bluff, but then offer help anyway. My role was to marshall resources for the community program and keep the worshipping community together. There was a new sense of freedom in my church work: More risk had a curious way of creating more freedom. Truth-telling became a homiletic necessity and that made it easier to hang onto my integrity. I put up a hand-lettered sign in the parsonage hallway: “Integrity means being true to your identity” — our Christian identity.

Repentence on the March

Joel and George Hrbek, now director of the Lutheran Human Relations Commission, led a five-mile walk Good Friday walk from Ridgeland Avenue to Walther High School as a confession of racism. Joel carried a processional cross made by Hilmar Sieving.

After the riot we were faced with the issue of survival as a congregation at a new level. This was coupled with the question of the survival of the spirit. My self-image was that of a little Dutch boy with his finger in the dike holding back the flood waters, only to look up and see the waves coming over the wall instead of just a trickle of water through it. Already middle-class black families were moving out of Englewood — a second migration that brought more physical changes. Even black members of Our Redeemer were moving farther south into better, more stable neighborhoods. Englewood became the neighborhood with the highest concentration of welfare recipients in Chicago. There were a host of transfer request from white members. I was told, “Our Redeemer is no longer our church. It has been taken over by the Parker students. You don’t care about the white members. You are the one who is racist.”

Good Friday came upon us. George Hrbek and LAC members, some who were on the faculty at Concordia Teachers College in River Forest, organized a march in the western suburbs to confess racism and promote racial tolerance and peace. The march started at the Ridgeland Commons park at Ridgeland and Lake Streets, six blocks from where I grew up in Oak Park at 623 North Ridgeland. Sue in her pregnant state did not join the walk, but waited at Mimi’s house praying for our safety. She drove the VW with Philip out to Maywood and welcomed us at the conclusion of the march. Her prayers were answered as we marched five miles down Lake Street without incident. I carried the processional cross from Our Redeemer that Hilmar Sieving had made. The march ended up on the grass outside of Walther Lutheran High School, from which I had graduated in 1957. I couldn’t help but take stock of how much I had been radicalized since that unreal but blissful era and how my perception of both church and world had changed.

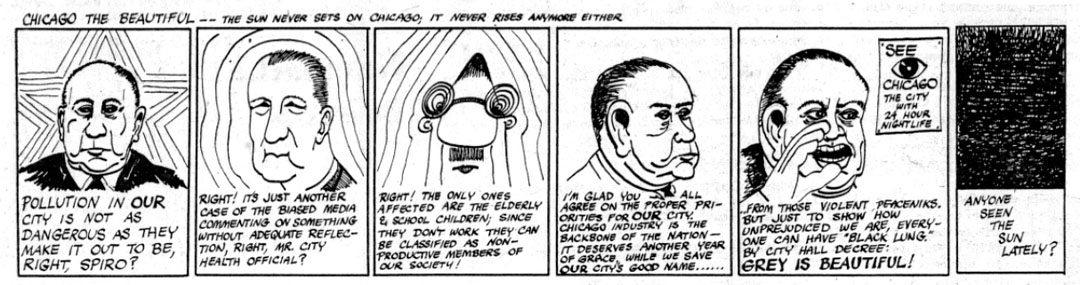

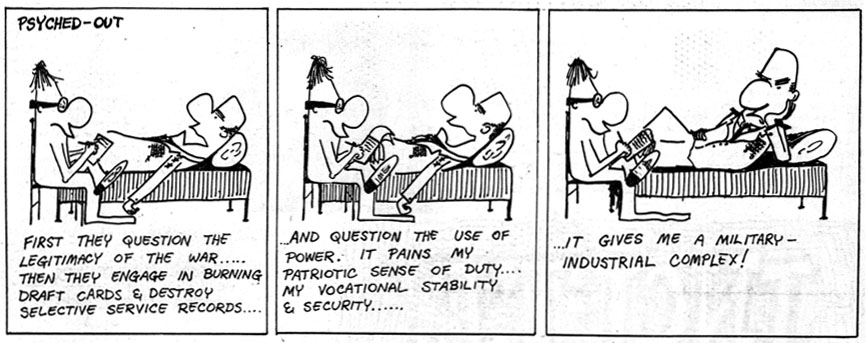

My old instinctive release from stress was to draw cartoons, something I’d done at the seminary (which had its own stress agents) and was tempted to take up again. The pen is mightier than the sword. George Hrbek was printing an underground newspaper for Lutherans, an outgrowth of LAC, and enlisted me as head cartoonist. It was one way to exhibit the technique of reversal: Whites loved their guns, but when black power advocates brandished their weapons, whites reacted with fear and demanded control by authorities. Reversal exposes racism: A white man in a black house juxtaposed with a black man in the white house. I put the drawing board Sue gave me as a birthday present the first year of our marriage to good use, and the ink started flowing.

It was imperative that we conserve congregational resources, trying to get our daily and Sunday functions back to “normal.” The Altar Guild of Our Redeemer held their 47th anniversary dinner — a span of faithfulness that needed to be celebrated. I gathered a good adult membership class together. We held a scholarship conference for high school students, informing our teens where the financial resources were to be found for college tuition. The congregation started a scholarship fund of its own to put some money where our mouth was.

In May we held a “Thanksgiving Dinner” which was an attempt to bring together the scattered remnant of Our Redeemer, and even entice some disaffected members to show up. Everyone who attended worked hard at the “black and white together” theme. Barbara O’Banion and Tom Gieschen sat down together on the piano bench for some impromptu improvising. It was musical fun. The kitchen crew enjoyed washing dishes together and hammed it up for my 8mm movie camera (see The Our Redeemer Story now on CD). Neighborhood children ran in and out, happy to be at the banquet. It was a family affair, successful because most of the people were finally given an opportunity to affirm each other, black and white, rather than have their choices and tastes dictated by outside forces. It was good to express unity rather than be the victims of separating forces. But unfortunately this was only a brief interlude.

Next: The Chicago Memoirs of 1968 (Part Five)

|