|

The Chicago Memoirs:

Our Redeemer Lutheran Church, 1967-1972

Chicago, South Side, 1970 (Part Two)

“I heard a crash coming from the Sorber building next door. I opened the side door to the alley between the church and the apartment building just in time to hear another loud crash and see a cast iron radiator come flying through the window and land in the vacant lot beneath. The building strippers were at it again, ripping off MY neighborhood.”

— Joel Nickel, The Chicago Memoirs

On Sunday, May 3rd, we celebrated our first Earth Day service with a litany that called for the care of the Earth. Ecological concerns were coming into view, thanks to Rachel Carson’s book, “Silent Spring.” Our neighborhood was an ecological disaster zone. Nothing grew on the debris-strewn vacant lots except weeds. So this Sunday everyone came to church in work clothes. We celebrated the Eucharist and then moved outside with brooms, shovels, rakes, and trash cans. We were joined by George Hrbek and his group from the Hyde Park “mansion.” We cleaned up three vacant lots, stacking trash by the curb for city garbage pick-up (which they finally accomplished, thanks to our prodding, three weeks later). We planted two trees, rose bushes, flowers and liberally spread around some grass seed. We swept the church parking-lot (the neighborhood playground) of broken glass which filled two large trash barrels. I finally removed the last vestiges of barbed wire still left on the chain link fence in back of the church building. The seeds, flowers and two trees were our offering of the morning, having been blessed in church, but that didn’t do much to insure their survival during the coming hot summer months with the increase in children traffic.

In fact the very next week I came out of the parsonage early one morning only to see one of our bright red geraniums walking down the street in the hand of a little first grade girl. “Honey,” I called after her, “where are you going with that flower?” “To give it to my teacher,” was her cute reply. The flower, roots and all, was still intact. “Please bring it back here,” I pleaded, “and I’ll show you some other flowers to take instead.” We reinserted the geranium into the soil in front of the parsonage, and I showed her how to pick pansies that were plentiful over by the fence. “Some flowers are for picking,” I explained, “and some are just for looking at.” She happily took a handful of colorful pansies to her teacher, and, as I might have predicted, pansy-picking suddenly became a popular pass-time for the children of Harvard Street. Flowers were a new thing. A rose can grow in Englewood, a sign of hope.

Mrs. Hans Poetsch paid Our Redeemer a visit in May. Her husband was the Lutheran Hour speaker in Germany and was presently taking courses at our seminary in Springfield, IL. Mrs. Poetsch had a social work background, and was interested in investigating how our urban churches related to the urban poor. Her main interest was our breakfast program which Otis had put together earlier that spring. It took a lot of coordinating on Otis’ part because three different groups were “sponsoring and supplying” the breakfasts: a group of students from Englewood High School, the EWRO, and the Black Panthers. Although they were dependable, we felt it would be best if the Panthers didn’t have full control of the program because we weren’t sure what our relationship with them would turn out to be. The Panthers were the ones to staff the breakfasts, doing an excellent job of preparing well-balanced meals as well as “recruiting” the foodstuffs. I never asked questions about where all the eggs, pork sausage, milk, cereal, and orange juice came from. They brought some food in bulk with contributions provided by “businessmen.” Other food was donated to the Chicago Panther group and then distributed to their various feeding stations. Our Redeemer provided bread. At its height there were about 70 children eating in our parish hall every weekday morning before they went off to school. You can’t learn on an empty stomach. The children were taught to be respectful of each other, not to waste food, and to come and go in an orderly manner.

Among the militant Panthers there was one red haired black gal who was especially effective in her love of children, but one day she was no longer present. It seems like the Panther Party in Illinois was going through a purge, and a strident militancy became evident. Up until this time the breakfast program wasn’t conducted like a “soup kitchen” — first listen to a sermon, then you get to eat. Now the posters started to appear. The pictures of Malcolm and Martin were fine, but the posters depicting Panthers in various military attire with the imperative, “Pick up the gun!” were out of line in our church building. There was even some “boot camp” type of “hut-two-three-four” marching around the parking-lot before breakfast that I put a stop to. I exercised censorship and took down the offending posters, and explained to the Panthers that black power, black pride, and black history were fine, but nothing advocating black violence would be tolerated on church premises. There was an uneasy truce. Feeding children was our top priority which the Panthers also shared. There is a very interesting footnote to this story that we’ll save for the Postscript, about one breakfast-serving Panther who later becomes famous in Illinois politics and returns to this scene as the pastor of the “Beloved Community Church”, formerly Our Redeemer. His name is Bobby Rush.

Of course Mrs. Poetsch didn’t observe any of this controversy, only the breakfast program which during her visit ran smoothly. Months later she sent me a woodcut reproduction as a gift along with a magazine copy of the article she wrote: “Früstück in der Kirche” (“Ein Pastor in Chicago kämpft gegen den Hunger der Schwarzen”). That summer when Tom Gieschen took his Concordia ‘Kapelle’ on a round-the-world concert tour, they found a copy of a Lutheran German newspaper with a front page story about Our Redeemer and its breakfast program. Thanks to Mrs. Hans Poetsch, we had international notoriety.

We got a phone call from his mother. Bruce Chapman was locked up in the Audy Juvenile Home. Between Don Marxhausen and myself we tried to assist him in getting released, paroled to our custody and supervision. We succeeded, even with his court date pending, primarily because of over crowding at the Audy Home. Bruce was an active and faithful Christian — one of our acolytes, center on the basketball team, and a student at Crane Tech High School were he was arrested for taking part in a student demonstration. Bruce claimed he was just a bystander. I often marveled at his courage and ability to avoid the intimidation of the D’s. One Sunday morning as Bruce was walking to church, a car of gang members drove up, asking where he was going so early. He told them. They leveled a gun at him, and demanded that he join the D’s. Bruce just kept walking. The gun came out the window again, and this time they fired, intentionally missing Bruce but trying to frighten him. Bruce didn’t run; he just kept walking. The Christian community at Our Redeemer meant something to him, and now it supported him too.

On Pentecost we confirmed Tim Weaver and Valori Armstrong. For Tim it was a passport to Luther High South, since the congregation paid part of his tuition. Valori, on the other hand, was active at Our Redeemer, helping her mother with the VBS program and joining in as an active member of the youth group. We were also in the process of repairing the holes in the massive stained glass windows over the front doors of the church. The north side windows had a plexiglass protective covering, but the streetside windows, high above the entrance, were vulnerable to rocks and stones. The financial “bite” came to $20 a hole and we spent $600 on window repairs — about 30 holes. The “Cathedral of Gospel Art” was expensive to maintain; we would rather spend our money on people. It seems to be easier to raise money to build monuments rather than to help people; we tried to reverse that until the rain came through the windows.

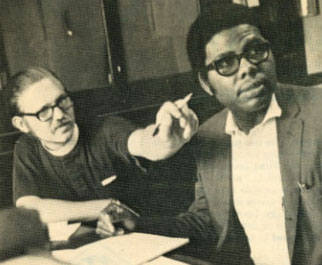

Joel and Otis Flynn

Joel and Otis Flynn at a meeting in the Our Redeemer parish hall.

Elmer Kramer stopped by to interview the people and staff of Our Redeemer for an article which eventually appeared in The Lutheran Witness” “Seventh in a Series of Outstanding Parishes — Our Redeemer Chicago.” His lead sentence: “Some veteran members of Our Redeemer Lutheran Church here say the congregation WAS an outstanding parish. A few English District leaders believe it IS an outstanding congregation. Some staff members contend it WILL BE an outstanding parish. It was a full two page spread, with some good photos. As things turned out, it was the last time the “Cathedral of Gospel Art” was written up until it changed denominational hands and became a non-denominational church, then getting press coverage from the Chicago Tribune in 2006 thanks to Bobby Rush.

The new arrivals into our transient neighborhood were mostly on welfare, and in a parallel development not much care was being given to any of the tenement buildings in blocks around the church. Thanks to Don Marxhausen’s energy and persistence we were able to revive talk about a housing program, church sponsored and FHA financed. Don, who always wanted to put talk into action, started looking around at tax records, trying to track down landlords. His search turned up a Mr. Sorber, whose apartment building was located along the south side of the church. It was in our self-interest to keep this building in place (it had suffered a basement fire earlier and had a multitude of vacant apartments that were later occupied by vagrants) because it shielded the south side stained glass windows which had no protective plexiglass covers that we couldn’t afford. Mr. Sorber’s building was all that stood between the windows and a pile of rubble at the corner of 65th and Harvard. Some lob shots had already found their mark but they were the exceptions. There was a lot of available ammunition.

One Saturday I was in the sacristy working on a sermon. I heard a crash coming from the Sorber building next door. I opened the side door to the alley between the church and the apartment building just in time to hear another loud crash and see a cast iron radiator come flying through the window and land in the vacant lot beneath. The building strippers were at it again, ripping off MY neighborhood. Without thinking things through, I angrily ran down the alley to the street, turned and bounded through the open door of the building (it was now always open, the lock having been broken last winter). I didn’t quite know what I’d do when I caught the building strippers, but calm reason was overtaken by blind rage. Didn’t anyone care that our community was being torn apart, the victim of scavengers and thieves? Moral indignation isn’t always rational. Lucky for me the strippers heard me coming, hid in a hallway, and exited the building as I was coming upon their “work” in a third floor apartment: the radiator was missing, waiting below for delivery to a junk yard to be sold for scrap. The lead weights in the window sash were missing as well as the sinks in the bathroom and kitchen. The apartment down the hall was not in any better shape. Sorber’s building was a wreck.

In conversation with Mr. Sorber, I found out that he had inherited the building from his father. He claimed dubiously that it contained too many family memories for him to visit frequently, so he paid a management firm to maintain the building and collect the rent. The management firm bilked him for repairs that were never made (I saw the receipts, and his claim was correct, but his lack of vigilance was his own fault). When one of the tenants had a fire in a basement apartment the fire was extinguished with little smoke damage to the rest of the building, but the basement apartment was uninhabitable. Sorber had it boarded up, which was a sign to his more stable tenants what his intentions were. Now Sorber wanted to give the building to the church as a tax write-off as it was less than 40% occupied (60% was required to break even), and even then by some non-paying street people. One apartment was occupied by two families. There was no grass left on the dirt of the front courtyard. His problem was that the Cook County assessor wouldn’t give property tax breaks to solitary slumlords (unless he had connections to an alderman).

We took Sorber seriously, went to Chicago City Bank to investigate if they would make loans to a private church-sponsored corporation for building rehab in Englewood. Their answer was a qualified “no,” at least for the building in question. Even at full capacity the building wouldn’t be able to repay the mortgage, given the amount of repair necessary. The building was a liability. Sorber was self-righteously incredulous, and even ventured to tell me how the church should get involved with urban problems and how he was involved with his church in Oak Park. I just looked him in the eye, shook my head, turned around, and walked back to the parsonage. Still, this was the beginning of Our Redeemer’s housing corporation.

How do you go about planning to rehab a neighborhood? Don began by canvassing the neighborhood, conducting his own title searches, and tried to line up people with certain skills to serve on the housing corporation board of directors. One of our lawyers who did pro bono work for EWRO began drawing up corporation papers. We submitted a proposal to Keys for Christ, the LCMS housing fund, asking for $5000 seed money. Our request was granted. The planning group interviewed some black architects and a mortgage broker. Don went ahead and started to collect options on property in the two block area around the church. We made some enemies, namely the three home owners whose small frame homes were sandwiched between the large stone tenements. They were opposed to urban renewal for obvious reasons, even though we invited them to join the planning group. Only one homeowner joined the group; he was the local precinct captain who earlier had angrily denounced me for not voting a straight Democratic party ticket in the national election. Sue and I were a blight on his record of posting a 100% democratic precinct “landslide.” So much for the secrecy of the ballot box and the privacy of the voting booth.

One bright spot was finding the “Environmental Seven”, a black architectural firm whose projects under construction looked substantial and were aesthetically attractive. We were at a crossroads: if the neighborhood continued to slip into oblivion there would be no housing and no people. No people — no church. One thing was certain: the neighborhood had viability — good mass transit, accessible manufacturing jobs, and a near-by shopping center. We thought of ourselves as a grass-roots oriented, peoplepower group, determined to control our own destiny, grab the bootstraps and pull up (that just about covers all the popular liberal jargon of the day). But all our hard work and dreams came to an end in November 1971 when President Nixon ordered a freeze on all FHA guaranteed loans, especially those going to urban areas that didn’t vote for Republican candidates (Daley was no friend of Nixon’s, having raised the dead to vote and defeat “tricky Dick” in his race with Jack Kennedy back in 1960). We were at a standstill.

I kept up a faithful schedule of visiting shut-ins, delinquent members, and making hospital calls. I attended the English District convention in Ann Arbor and then flew to St. Louis for a workshop required for those who were writing lessons for the Mission:Life curriculum. I had agreed to write the first quarter 8th grade lessons. We met at Fordyce House south of St. Louis near the Mississippi River, far from any urban environment. My urban slant to the lessons would later be revised to a more rural bias by the BPE editors, so that all I got out of the workshop was a serious case of infected insect bites that came from a walk in the woods. Chiggers! While I was at this two week workshop, our janitor, Cleo Lake and a friend were busy ripping off (literally) Our Redeemer. They tore down all the copper downspouts, which from a roof six stories above the ground involved a lot of copper, whose price was skyrocketing at junk yards. This was building stripping applied to the church, only the church building was still occupied. We caught Cleo, fired him, and went to the police. That began a long series of court hearings, during which time Cleo was to be paying for the damages. But he was no longer employed and we were lucky to get $60 from him. Water running off the roof in a thunderstorm made for interesting, cascading waterfalls all around the building. We replaced the copper downspouts with galvanized ones.

After worship on Sunday, July 12, Sue and I took a three day mini-vacation to the Illinois Beach State Park lodge in Zion on Lake Michigan. We moved our suitcases into the airconditioned room, gazed down at the swimming pool beneath our window, and stretched out on the bed in each other’s embrace. Just then the phone rang. It was Don Marxhausen, letting us know that the parsonage had been broken into and a number of items were missing — the TV, a slide projector, radios, and other hockable goods. My study was a shambles. I told Don not to worry, but to lock the place up, secure the second story bedroom window (the place of entry, which meant that the intruder had to scale the iron bars over the dining room windows, crawl onto the tiny roof ledge over the bay window, and pry up the bedroom window — all this in broad daylight, which meant that there were witnesses). Our valuables — art work and photographs — were not disturbed. We still felt safe, ripped off only once so far while living in a high crime neighborhood, and so stayed put at the lodge, relaxing and enjoying the pool. Nine months later Daniel Kipp was born.

Detective Rabino visited us the following Saturday and we gave him the serial numbers for most of the lost items. On the last day we spent in Englewood, even as the movers were loading our household items onto the van for the trip to Champaign, I received a phone all from the Chicago Police. They had recovered my slide projector, a gift from Sue, in a raid on a pawn shop and identified it by its serial number. I quickly drove to the police warehouse to pick it up, with sincere thanks. It wasn’t in bad shape, a fitting irony for our departure from Englewood almost two years after the robbery.

Sixty-five children were enrolled in our evening summer VBS. One night as we were herding children out the door (they would have stayed all night if we permitted it), one of the nine year old boys gave the parish hall room a parting shot of mace. Since it was hot and we had a large fan going, the mace was quickly blown over the entire parish hall room and left the entire staff in tears. It all happened so quickly, and little Stanley, laughing all the way, made his quick exit after macing us. We found the empty mace can outside where Stanley dropped it. It had the label of the Chicago Police on it. How Stanley came to obtain this crowd-control device we would never know. There was never a dull moment teaching the Bible in the ghetto.

Mrs. Luther Schuessler died and her funeral service was held at Our Redeemer. The texts, liturgy and hymns were parallel to that of her deceased husband, Luther’s service. It was a moving service. The Schuessler family had invested so much of themselves in the parish and its people through the “golden years” of its history, and that investment was treasured by many people and needed to be celebrated. The present problems of Our Redeemer were no fault of the Schuesslers; parish pastors always shoulder responsibility and learn to handle criticism with grace. I may not have measured up to Luther Schuessler in many member’s eyes, but then, our circumstances were different. This funeral marked the “end of the era” as time moved relentlessly forward, reminding us that in this transient world there are no lasting monuments.

The summer wore on, its heat locked into the asphalt parking lot, broken only by children who opened the fire hydrant in front of the parsonage, playing hide and seek with firemen who periodically came by to shut it off. The children showed a lot of creativity — lacking the playthings of most park playgrounds, they manufactured their own. They placed an old discarded tire around the fireplug, wedged a big plank between the tire and the base of the hydrant, and the gushing water, hitting the plank, would spray out in all directions, covering the whole street. Passing cars received an unplanned car wash, and not everyone rolled up their windows in time.

We held a multitude of meetings with housing people — the alderman, who had his fingers in the housing pie as a “consultant” whose blessing was needed to move plans forward, Walt Marshall, Bill Wallace, Fred Henderson, and Cliff Gramer, our lawyer. Carl Roemer bunked with us at the parsonage for a couple of weeks while taking courses at LSTC. He reflected on how tough the kids in the “hood” really were after getting kicked in the ass by a little girl that afternoon without provocation. The “whitey go home” sentiment surfaced in the most unexpected ways.

Next: The Chicago Memoirs of 1970 (Part Three)

|