|

Wilhelm and Frau Erica:

Staying the Course, Righting the Ship

I. Kendallville, Indiana

Two generations of Muellers emigrated together and gained a precarious foothold on American life near Kendallville, Indiana. If the business of emigration — selling the Bosenbüttel estate, transferring funds, booking passage for the family, finding a new home in Indiana — fell to Fritz and Johanne, the business of establishing the Mueller family in the New World fell to 19-year-old Wilhelm and his wife Adelheid. Much of this narrative, divided here into three parts, derives from three sources: Wilhelm and Adelheid’s son Ernst (Opa) Mueller, their daughter Frieda Mueller Feiertag, and their son-in-law Friedrich (Fred) Knief.

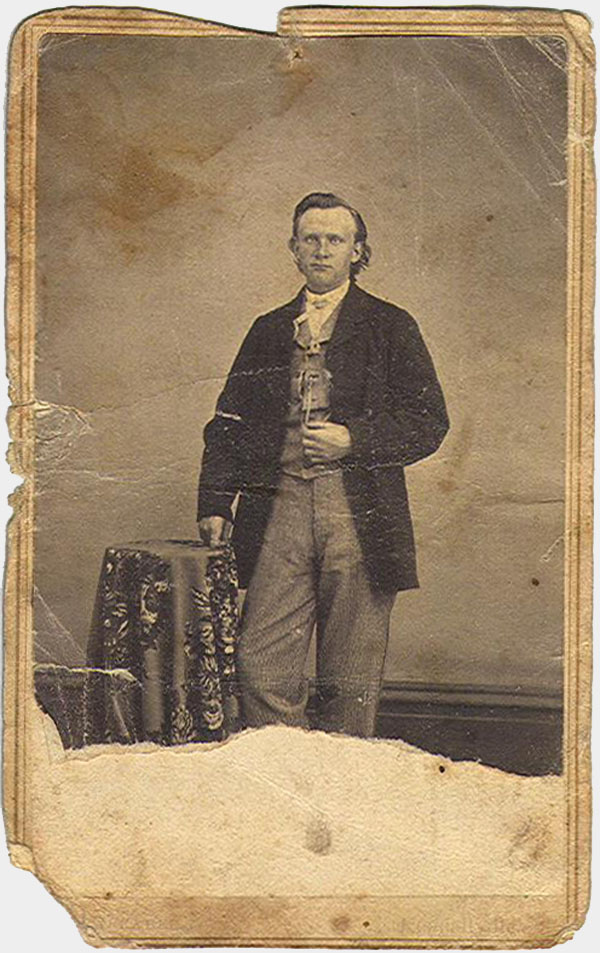

Portrait of the farmer as a young man A 20-year-old Wilhelm Mueller sent this photograph to his fiancée Adelheid (Frau Erica) Rickmeyer in Germany. Would she come to America and marry him, despite the reduced circumstances of the Mueller family? Photo: J.H. Labrabees (Kendallville, Ind.; May 21, 1867) Wilhelm had a long, hard pull. He arrived in Kendallville at age 19 with his parents and siblings in November 1865. His father, Fritz Mueller, had sold their Bosenbüttel estate and arranged for most of his fortune to be transferred to America through Bremen bankers. He converted the rest to gold and stuffed the coins into a money belt, which his wife wore on the trip to America.

On November 15, 1865, Fritz purchased a 530-acre farm to the east of Kendallville, Indiana, a deal that would prove disastrous. The agent who brokered the deal was a man named Frank Mitchell, who had been recommended to Fritz by a Lutheran pastor from Fort Wayne. The minister and the agent appear to have been dishonest men working together. There was an undisclosed lien against the entire property, so the land did not have clear title. Fritz paid cash, which soon disappeared. Family tradition says that the Lutheran pastor began driving around in a brand new carriage — his commission, they assumed.

Whether Fritz had any inkling of a problem is unclear; there is no hint of trouble in his journal. Within six months of striking that disastrous deal, Fritz,44, fell ill and died on May 6, 1866. Shortly after Fritz’s death, the bank foreclosed and dispossessed the Muellers of almost everything they had, even the family silver and linens, leaving them nearly in poverty. A small portion of the farm — about 110 acres, roughly a fifth of the original farm — was granted to Fritz’s widow, Johanne, under a heavy mortage. The whole mess landed in Wilhelm’s lap: paying off the mortgage, working the farm, raising his siblings, caring for his mother, starting his own family.

There is a notation in an index to court orders of the 1860s that on May 22, 1866, Fritz’s great friend from Germany, George A. Saxer, was appointed guardian of eight of the nine Mueller children (Theodora had passed her 21st birthday). Johanne’s son-in-law Ludwig Knief mentions Saxer’s support for Johanne and the children with great admiration in his Lebenslauf. The actual paperwork of that court appointment was lost when the Noble County courthouse burned to the ground.

The older Mueller daughters married, and each took a younger sibling along to her new home, reducing the burden on Wilhelm. Theodora married Pastor Ludwig Knief in May 1868 and took her brother Hans, then about 10, to Gasconade County, Missouri, where he stayed until after his confirmation. He later studied for the Lutheran ministry and became pastor of St. Luke’s Church on Belmont Avenue in Chicago. Elizabeth married Gottfried Lehnigk, a Lutheran teacher, in August 1868, and took her brother Erich, then about 20, with her to Perry County, Missouri, where Erich later married.

While the Mueller family was still in Germany, Wilhelm had met and become engaged to Adelheid Rickmeyer. Adelheid was working as a governess then but was also trying to establish a career as a writer. (Frau Erica, the pen name she adopted when she was 16, derives from Erikablüte, the heather that grew in her beloved meadows.) She had had her share of difficulties. Her mother, Doris Mahler, died when Adelheid was a child, and her father Ernst Rickmeyer remarried. The archive has no information on the reason for the change, but the three Rickmeyer children — Carl, Adelheid, and Marie — went to live with their maternal uncle Klaus Mahler and his sister Marie at the Efeuhaus (Ivy House) in Freiburg an der Elbe. (Klaus was apparently unmarried and had no children of his own. Decades later, Adelheid’s children would receive shares of his estate in the Erbschaft.) Whatever plans Wilhelm, 18, and Adelheid, 20, may have made were set aside in the summer of 1865, when the Mueller family emigrated to Indiana.

About a year after Fritz died, when the Mueller family was settled on what was left of the farm, Willhelm sent for Adelheid. Would she join him in America? She left Germany from Hamburg on 28 September 1867 aboard the steamship Germania in a second-class cabin (zweite Kajüte). She traveled alone from Germany, a 22-year-old woman. In a handwritten memoir, Adelheid’s daughter Frieda (Tante Fieks) said the ship’s captain [passenger lists mention a Capt. Schwensen] was smitten with Adelheid, persistently disparaged the life of a farmer’s wife, and tried to convince her to stay in New York, but she pushed on. A Lutheran minister met her ship and helped get her and her belongings onto a train bound for Fort Wayne, Indiana. Adelheid had been expecting Wilhelm, but he could not afford the time and money to leave the farm.

Wilhelm and Adelheid were married November 28, 1867, despite his greatly reduced circumstances. Many stories arose from their wedding. The pies for the wedding dinner were baked and placed on the kitchen windowsill to cool ... and were promptly stolen by the Indiana neighbors.

A very poor, very happy young couple

Wilhelm and Adelheid with the first of their 10 children, Carl Friedrich Wilhelm, who died in infancy. Carl was born Oct. 16, 1868, and died Sept. 6, 1869. Photo: F.P. Ford (Kendallville, Ind.; May 11, 1869) It was German Lutheran tradition to take a collection for the poor at festive occasions. As the Klingelbeutel was making its way toward them, the Muellers realized that they did not have a single coin to contribute. Adelheid saved the day, sending a young child to her room to fetch her last dollar coin. Johanne, her mother-in-law, did the honors, taking the coin and announcing in a loud voice, “Im Namen der Familie Mueller,” as she dropped it in. Quite a come-down for the woman who two years earlier had arrived wearing a beltful of gold coins.

Wilhelm and Adelheid lived in the larger of two houses on the property, a typical gray-wood Indiana farmhouse in need of paint, according to photos. (Johanne lived in the smaller one with her daughter and caregiver Gertrude.) It was close to a dirt road. Eight of the young couple’s 10 children were born on the farm. Besides tilling the land, they raised cows and a flock of sheep. Records of the lambing operation exist in the hand of their eldest son Ernst (Opa Mueller), who kept score on the kitchen calendar: “Drei lebendig, eins tot” (three living, one dead). Wilhelm struggled to make a living from the farm and felt conscience-bound to share whatever income he netted with his brothers and sisters. (His younger brother Fritz helped him work the farm.) Wilhelm suffered badly from hay fever and wore a mask when he worked outside. It was a cash-poor life, but culturally rich. Wilhelm and Adelheid read Shakespeare aloud, and Adelheid instructed the children in many subjects, even attempting a bit of French.

Johanne died April 11, 1880, aged 60 years, by which time all but two of her children — Hans and Gertrude — were married and living on their own. Her death marked the end of the early years, the passing of the older immigrant generation. By then, Wilhelm’s brother Fritz had married Mary Mertz, a local girl whose resources were sufficient to finish paying the mortage and get a clear title to the Mueller farm 15 years after the swindle.

Wilhelm decided to save his health and leave farming to his brother. He moved into Kendallville proper late in the summer of 1885, taking a team of horses, a farm wagon, and probably a cow. He became a drayman in town, hauling freight with his team. A daughter was born after Wilhelm and Adelheid had moved into town.

Next: Careers in Chicago

|