|

McMillan Manufacturing Company

In September 2002, Molly Bigelow McMillan wrote the following historical account of McMillan Manufacturing Company, the corporate predecessor of McMillan Electric Company.

When World War II ended in August, 1945, Malcolm McMillan came home from Washington, D.C. where, since 1942, he had been in the Army’s Office of Procurement. Polio as a child kept him from active service. He went back to his old job at Gould Battery.

Dick McMillan came home from Hollister, California, where he had been poised to go to the Pacific with the Naval Air Corps. Although he remained in the Naval Reserve for almost ten years, the few months left of active service were fulfilled by checking in each day by phone with the Naval Air Station at the airport. His old job as a signalman on the Great Northern tracks was no longer appealing.

I was in the hospital in October with some complications following Charley’s birth when the brothers walked in carrying a toy duck pulled by a string. They had determined to go into business together and wondered what I thought of the possibilities of toy manufacturing. I did not have a thought one way or another!

“I was in the hospital in October [1945] ... when the brothers walked in carrying a toy duck pulled by a string. They had determined to go into business together and wondered what I thought of the possibilities of toy manufacturing.”

Fortunately, Malcolm’s father-in-law was an electrical engineer and he offered to design a fractional horsepower motor for them. A year’s worth of Dick’s naval pay and a bank loan, with my St. Paul Co. stock as collateral, were not quite enough to get started. (Our expenses were minimal since we were living rent-free with my mother.) Therefore they asked their Uncle Harry Mundy, successful in the construction business, for a $3,000 loan. He turned them down flat. My mother was a gentler sort and lent them the money.

Production was set up in my mother’s garage which was on Heather Place (now Floral) below the house at 530 Grand Avenue (now Grand Hill). The houses that are now across the way were not yet built. Dick’s job was to find the materials and machinery needed. He found old electrical wire at the dump, I believe. Laying it out on the bushes across the way, he then stripped it to provide the copper wire for the windings. Two surplus drying ovens he heard about were priced at $15 each, but before he could reach them they had been sold. They were sold once again before he was finally successful in purchasing them for $300. Those ovens were used continually until the new plant on the West Side was built in the late ’60’s.

Mr. Oppenheimer, a friend of the McMillans, took care of the incorporation of the company with its three partners. Mr. Schmidt, however, was a partner rather briefly. I do not remember the particulars of his leaving, but there was a small unpleasantness when he garnisheed our bank accounts, to Mal and Marnie’s embarrassment.

Sometime in the spring of 1946, the plant moved to the seventh floor of the Lindeke building at Fifth and Rosabel (now Wall Street). Two employees were hired: Dorothy Heckel as secretary and Dick Schowalter as production manager. Neither Dick nor Mal, of course, was sitting in an office. The three men were the production crew. A first order had come in, which I remember was for $50,000 worth of motors. I also remember Dick’s euphoria — we were on our way to riches!

“A first order had come in, which I remember was for $50,000 worth of motors. I also remember Dick’s euphoria — we were on our way to riches! ... [But] part way through production, the order was canceled.”

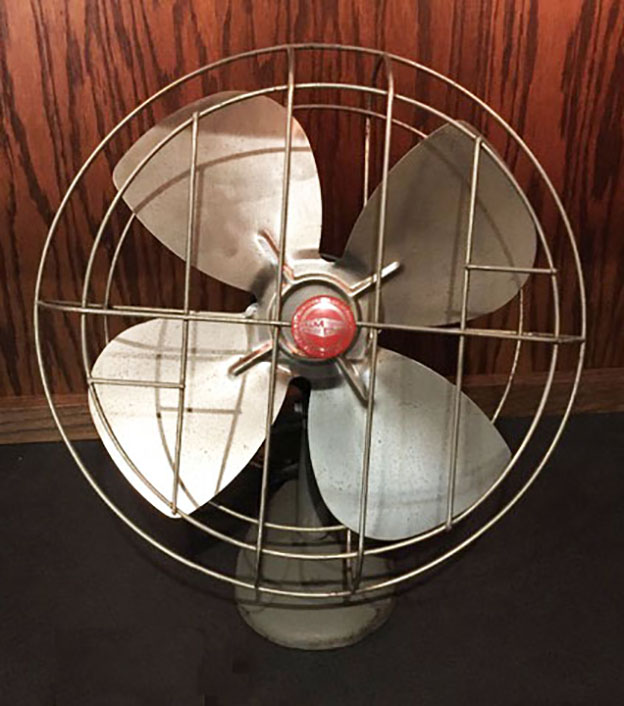

Part way through production, the order was canceled. So Mal designed a fan, and the University was asked to redesign the motor. Several thousand fans were sold, helping the company pay for its initial expenses and remain in business. (One fan remains on display today in the McMillan Electric Company Conference Room.)

Soon after that, W.W. Grainger came into the picture as the first high-volume customer. Grainger, a wholesale parts supplier, was the key to McMillan’s success because, for the first few years, they advanced production costs and were repaid through a discounted price.

The success of the company was also due to the way the employees were made a part of the operation. From the beginning, there were monthly meetings in which full discussion took place. Order strength, profits, losses, complaints, solutions were all considered. All worked together as a team. Ron Tschida, a brilliant young natural engineer was one of the early additions. Mal and Dick soon sent him to the University to take engineering classes, tuition paid.

The original When the company’s first order for motors was canceled part way through production, Mal designed this fan and McMillan Manufacturing sold several thousand copies of it to keep the company going. Mal was also an engineer, though without formal training. Dick was gifted in the financial and personnel areas, so they made a good team. Dick also understood the importance of keeping the bankers fully informed. In return, he was invited to become a member of the Board of the Grand Avenue Bank.

Their father had been one of three brothers who jointly inherited McMillan Pork Products. The strain that this had caused in the family made a buy-sell agreement between Mal and Dick of first importance. Insurance was purchased to undergird the agreement. For a while, every four years, they alternated the position of president. After Dick became a member of the Young Presidents’ Organization, he retained the title permanently.

It was not long before the Lindeke building was outgrown and McMillan Manufacturing moved to the Northern Jobbing building at 310 Broadway. They initially occupied the basement and the first floor, eventually expanding to all six floors. And that was where they fought off the memorable flood waters of 1965. Dick was able to get pumps quickly from the Lovering Construction Co. For twelve days the men in their hip boots kept watch on round-the-clock shifts. They had a rowboat tied up at the Fourth Street corner of the building for transportation.

Although men were required to run and maintain the large machinery, the dexterity of women was needed to assemble the motors. Most of the workers came from the East Side of St. Paul. One of the women, Alicia Doody, who was somewhat older than the other employees, was a character in her own right. The day after Dwight Eisenhower was elected president, bringing in a Republican administration for the first time in twenty years, Alicia came into Dick’s office. She was in tears because she thought that this Republican victory meant that the plant would close down. It was a first recognition for us of the gross distortions that are introduced into political propaganda. Intensely loyal, when Alicia retired, she refused her pension for almost a year. She was not to be persuaded that it was truly hers and fully earned.

“... they fought off the memorable flood waters of 1965. Dick was able to get pumps quickly from the Lovering Construction Co. For twelve days the men in their hip boots kept watch on round-the-clock shifts. They had a rowboat tied up at the Fourth Street corner ... for transportation.”

The announcement of bonuses, based on profitability, was a major event at the annual Christmas party along with the announcement of salary and wage increases. These parties were for employees only and a good time was had by all. With men in short supply, Dick got a workout dancing butterfly polkas with two partners at a time. Mal was apt to entertain with sleights of hand and palm readings.

By the end of the ’60’s McMillan Manufacturing was on the move again. This time they built a new plant on Port Authority property on the west side of the river near Holman Airport. By this time they also had a small auxiliary plant in Siren, Wisconsin, and McMillan Motores was operating as a joint venture in Mexico City. In addition, a small Board of Directors was appointed, made up of friends who were fellow YPO’ers, Bob Linsmayer, Daniel O’Brien, Paul Schilling and Bob White.

Soon, however, it was evident that further expansion would require more cash input than was feasible and so the decision was made in the summer of 1972 to sell the company for about $6.8 milion to W.W. Grainger. Mal and Dick each received 50,000 shares of Grainger stock. An article in the Wall Street Journal noting the sale (6/2/7) noted that McMillan had sales in 1971 of about $9 million. Grainger quickly combined the McMillan firm with Doerr Electric Company, another electric motor company they had recently purchased.

Mal promptly used a portion of his share to buy a Chrysler agency in Forest Lake, automobiles being always his first love. Dick gave a chunk to the House of Hope in memory of his parents, and went off to play golf. I shall always remember the shock on Cal Didier’s face when he realized the size of the sum that Dick was casually mentioning to him after the church service ($200,000).

Though the four older children had each spent a summer at McMillan, only Doug had sustained an interest, and so, after graduating from Colby in 1972, he went off to Milwaukee as a salesman for Doerr Electric.

“Sadly, Grainger mismanaged McMillan badly ... and in early 1975 Grainger simply closed the plant. During that time, Doug had written so many letters to Doerr about how they ought to be running McMillan that he got himself fired.”

Sadly, Grainger mismanaged McMillan badly. Credit to customers was substantially reduced, the computer was moved off-site, personnel meetings were discontinued among other things. Customers moved elsewhere and in early 1975 Grainger simply closed the plant. During that time, Doug had written so many letters to Doerr about how they ought to be running McMillan that he got himself fired.

Grainger hoped to sell the entire company, but was not successful. Turning to plan B, they advertised the individual lines for sale. Dorothy Heckel and most of the supervisors were retained so that the machinery could be shown to those interested. In between times, they played a lot of chess and occasionally Doug would go down and play with them.

The two-pole, four-pole and PSI lines were sold off and then Dick and Doug began to contemplate buying the six-pole line. This happened to be the line that made the fan motors for Lakewood Manufacturing in Chicago, another major customer. Grainger, however, did not wish to give Wall Street the impression that they had failed, so Dick asked Mauricio Merikanskas of McMillan Motores in Mexico to act as a negotiator. Eventually, in March of 1976, they were able to repurchase the six-pole motor fan line and $174,000 worth of inventory for $500,000. Much of the machinery had been disbursed and was returned from several Doerr plants. The small plant in Siren was not included in the sale. Several Doerr Electric invoices to McMillan Motores were cancelled, evidently as a fee for services rendered.

A building was purchased in the Woodville, Wisconsin, Industrial Park, the machinery was moved in, and a large van was purchased. Most of the supervisory staff and Dorothy Heckel, Dick and Mal’s secretary, were willing to drive to Woodville to start things over again. Many of these employees, now of the newly incorporated McMillan Electric Company, drove out from the city together, continuing their camaraderie of many years. A call to Carl Krause, president of Lakewood, had resulted in the promise that Lakewood, for the first year, would take all the motors that could be produced. Additional employees from the Woodville area soon began to be hired.

Under Dick, and now Doug’s, able leadership, the new company has grown and greatly expanded. They not only make fan motors, they are now the largest producer of treadmill motors in the country. We can all be proud.

— Molly Bigelow McMillan

September 6, 2002

|