|

James Hilbert Nickel: Artist in Venture

I. Oak Park, Illinois

What follows is a fraternal Festschrift written by brother Joel in celebration of the artist’s 55th birthday, November 30, 1998. The unpublished text was written for readers who may have encountered the work but not the artist, which accounts for the formal references to “Nickel” rather than the more familial “Binyon.”

He recycles, reclaims, renews

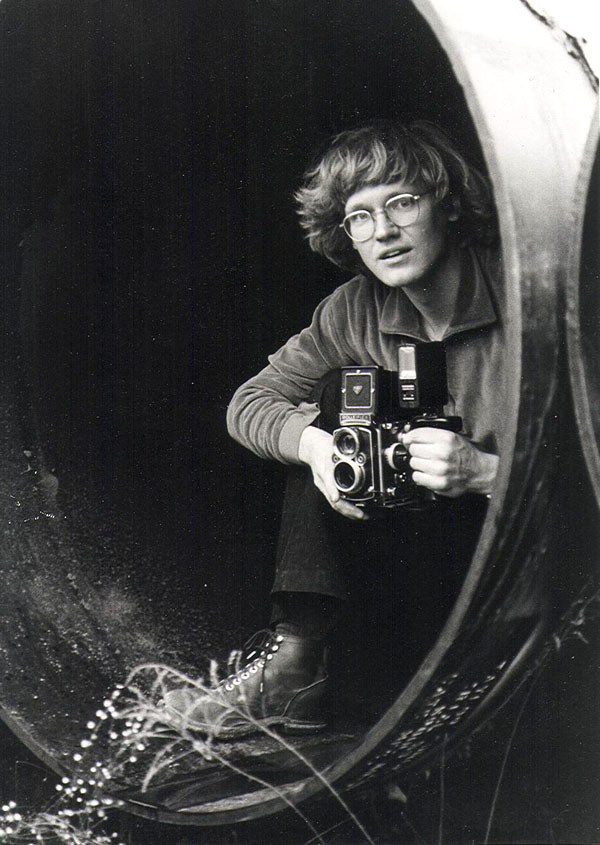

Jim Nickel on the grounds of Standard Pipe Protection Co., in Brentwood, Missouri. Industrial areas were a favorite for photographic excursions; industrial castoffs were a primary source of raw materials.

Photo: Mark Nickel

Jim Nickel is an artist who loves the heft of wood and the intricacies of shape, shadow and color. His artistic antenna picks up abnormalities, notices intrigue, weathering, and pattern, enabling him to carry forward a battle between concept, word and image. He likes to look beneath the surface of things, peer through the horizontal layers, and reposition the pretentious logos which grab at our awareness. He has an obsession with transforming the given — cutting, shaping, and rearranging the pieces while “losing only the sawdust.” He recycles, reclaims, and renews material, from oak planks found in an industrial dump to fossilized dinosaur dung from an Arizona desert. He picks up flotsam and jetsam — a canoe paddle which he cut up and reformed into a “progression piece” or the broken and discarded parts of a handtruck which became the criss-crossed intersections of a wall sculpture. Likewise his paintings are layered with intricate “cosmic cross-hatchings” applied over large flat geometric forms, creating a sense of depth. Art is life and life is art, intermeshed and ripe with meaning.

James Hilbert Nickel was born in 1943 and raised in Oak Park, Illinois, only two blocks from the William G. Fricke house, designed and built in 1901 by Frank Lloyd Wright. As a youngster one snowy winter day, he rang the doorbell of that home, offering to shovel the sidewalk for 75 cents. The offer was accepted. This was a corner lot, and forty feet into the project of moving heavy snow, Nickel ran out of energy, whereupon the homeowner invited him inside — Nickel’s original, secret objective. With a cup of hot chocolate in hand and a one dollar bill in his pocket, his eyes recorded the treasures of the Wright interior — the oak furniture, the richly paneled ceilings and walls, the delicate fenestration, and the strong horizontal lines of right angle geometry. Wright’s work has an organic continuity with the site, building “in the landscape not on it,” that provided a strong attraction. Nickel later photographed all thirty-two buildings in Oak Park and River Forest designed by Wright, preferring the winter view when leafless elm trees left the strong architectural lines unobstructed.

Nickel’s early fascination with Wright’s architecture found an outlet in the chair series he has worked on over the years. Beginning with the Gorilla Chair of 1965 to the Chicago Chair of 1986, these wooden chairs all have a solid link to the ground they stand on as part of the landscape. The huge Three Chairs, left (15’ x 8’ x 8’), exhibited at the Queens College “Ways of Wood” show in 1985, are three chairs of similar shape but different scale stacked one upon the other, fit for a Queen. This time Nickel took a respite from the stark right angles he had favored and gave these chairs a feminine, graceful flowing line in the arms. The triple stack ascends to a point of royal importance and establishes the prominent presence of the sculpture. The Black Tar Chair of 1982 was part of “The Monument Redefined” group show along the Gowanus Canal in Brooklyn. Much larger than life-size, this plywood chair was an open invitation to graffiti artists to make their mark, so Nickel covered it with tar. The chair couldn’t be sat upon without leaving a stain — a utilitarian object rendered unusable by size and surface. The vandal audience later torched the chair as their final aesthetic response, and all that was left of the Black Tar Chair after the show was a pile of ashes. All these chairs are architectural sculpture growing out of the earth, anchored by sturdy timbers. The Chicago Chair of 1986 consisted of four stacked chairs, each of them expanded in size from a “truncated triangle” module in a system of perfect gnomic growth. The impact is monumental even though the piece was exhibited indoors.

The original chair epiphany happened during a trip to New York City in the early 1960s when Nickel discovered an icon of the De Stijl movement — the Gerrit Rietveld Red/Blue Chair (1918-1923) in an exhibit at MOMA. He and a friend furtively measured its dimensions, and he returned to Oak Park to build a replica with the primitive tools at his disposal. The black superstructure, primary colors and hard right angles caught his eye and fit into his quest for a foundation from which a statement about essentials could be made. Chairs have a supportive function — they secure a place and provide opportunity for contemplation, parallel to the way in which Nickel wished his art to function. Thus the chair constructions are the springboard for much that comes later in Nickel’s sculpture. It is a short aesthetic distance from the early chair sculptures to the wood constructions which he produced at his first studio in an industrial area in Brentwood, Missouri, a suburb to the west of St. Louis.

Next: Brentwood, Missouri

|