The Frau Erica Project

Muellers in America:

The first 159 years

About the site Users guide

Contact the archivist

Go to: Ur-Muellers

Index of persons

Index of texts

Photo galleries

The Mueller lexicon

Back to family tree

My home page

Struwwelpeter English

German

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

How Der Struwwelpeter came to be

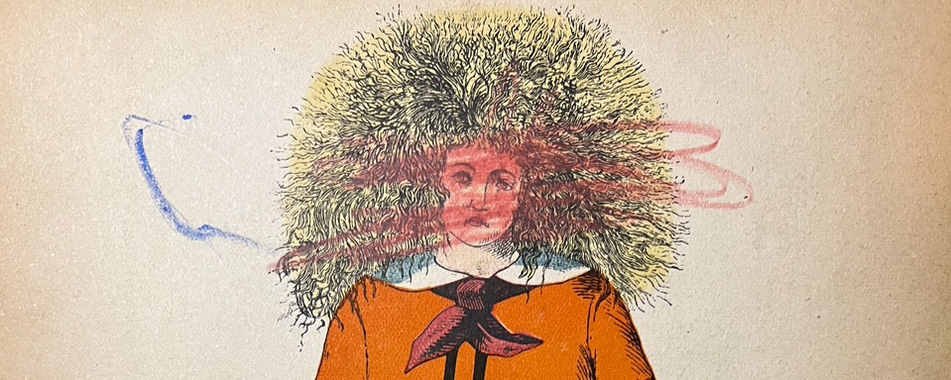

Beginning as a Christmas present in 1844, Struwwelpeter became one of the most successful children’s books ever. It went through hundreds of editions, was translated into all European and several other languages, and was a familiar part of life in the immigrant German home. This account, written by the author Heinrich Hoffmann, appeared in 1867, marking the 100th edition of the book.

|

|

Dr. Heinrich Hoffmann, der Verfasser des

Struwwelpeter, erzählt dessen Entstehung wie folgt:

Gegen Weihnachten des Jahres 1844, als mein ältester Sohn drei Jahre alt war, ging ich in die Stadt, um demselben zum Festgeschenke ein Bilderbuch zu kaufen, wie es der Fassungskraft des kleinen menschlichen Wesens in solchem Alter entsprechend schien. Aber was fand ich? Lange Erzählungen oder alberne Bildersammlungen, moralische Geschichten, die mit ermahnenden Vorschriften begannen und schlossen, wie: “Das brave Kind muß wahrhaft sein”; oder: “Brave Kinder müssen sich reinlich halten” etc. – Als ich nun gar endlich ein Foliobuch fand, in welchem eine Bank, ein Stuhl, ein Topf und vieles andere, was wächst oder gemacht wird, ein wahres Weltrepertorium, abgezeichnet war, und wo bei jedem Bild fein säuberlich zu lesen war: die Hälfte, ein Drittel, oder ein Zehntel der natürlichen Größe, da war es mit meiner Geduld aus. Einem Kind, dem man eine Bank zeichnet, und das sich daran erfreuen soll, ist dies eine Bank, eine wirkliche Bank. Und von der wirklichen Lebensgröße der Bank, hat und braucht das Kind gar keinen Begriff zu haben. Abstrakt denkt ja das Kind noch gar nicht, und die allgemeine Warnung: “Du sollst nicht lügen!” hat wenig ausgerichtet im Vergleich mit der Geschichte: “Fritz, Fritz, die Brücke kommt!” |

Dr. Heinrich Hoffmann, the author of Struwwelpeter,

tells the story of its creation as follows:

Toward Christmas of 1844, when my eldest son was three years old, I went into town to buy him a picture book as a festive present, as would seem appropriate to the capacity of a little human being of that age. But what did I find? Long stories or silly collections of pictures, moral tales that began and ended with admonishing precepts such as: “The good child must be truthful”; or: “Good children must keep themselves clean.” — When I finally found a folio book in which a bench, a chair, a pot and many other things that grow or are made, a veritable repertory of the world, were drawn, and where each picture was neatly marked: half, a third, or a tenth of the natural size, my patience ran out. To a child, for whom one draws a bench and who is supposed to enjoy it, this is a bench, a real bench. And the child does not have and does not need to have any concept of the real-life size of the bench. The child does not yet think abstractly, and the general warning: “Thou shalt not lie!” has little relevance compared to the story: “Fritz, Fritz, the bridge is coming!” * |

|

Als ich damals heimkam, hatte ich aber doch ein Buch mitgebracht; ich überreichte es meiner Frau mit den Worten: »Hier ist das gewünschte Buch für den Jungen!« Sie nahm es und rief verwundert: “Das ist ja ein Schreibheft mit leeren weißen Blättern” “Nun ja, da wollen wir ein Buch daraus machen!”

Damit ging es nun aber so zu. Ich war damals, neben meinem Amt als Arzt der Irrenanstalt, auch noch auf Praxis in der Stadt angewiesen. Nun ist es ein eigen Ding um den Verkehr des Arztes mit Kindern von drei bis sechs Jahren. In gesunden Tagen wird der Arzt und der Schornsteinfeger gar oft als Erziehungsmittel gebraucht: “Kind, wenn du nicht brav bist, kommt der Schornsteinfeger und holt dich!” oder: “Kind, wenn du zu viel davon issest, so kommt der Doktor und gibt dir bittere Arznei, oder setzt dir gar Blutegel an!” Die Folge ist, daß, wenn in schlimmen Zeiten der Doktor gerufen in das Zimmer tritt, der kleine kranke Engel zu heulen, sich zu wehren, und um sich zu treten anfängt. Eine Untersuchung des Zustandes ist schlechterdings unmöglich; stundenlang aber kann der Arzt nicht den Beruhigenden, Besänftigenden machen. Da half mir gewöhnlich rasch ein Blättchen Papier und Bleistift; eine der Geschichten wie sie in dem Buche stehen, wird rasch erfunden, mit drei Strichen gezeichnet, und dazu möglichst lebendig erzählt. Der wilde Oppositionsmann wird ruhig, die Tränen trocknen, und der Arzt kann spielend seine Pflicht tun.

|

When I came home, however, I had brought a book with me; I handed it to my wife with the words: “Here's the book I wanted for the boy!” She took it and exclaimed in surprise: “It's a notebook with blank white pages!” “Well, let's make a book out of it!”

But that's how it went. At that time, in addition to my job as a doctor at the mental hospital, I was also dependent on practicing in the city. Now the doctor's dealings with children from three to six years of age are a thing of their own. In healthy days the doctor and the chimney sweep are often used as a means of education: “Child, if you are not good, the chimney sweep will come and get you!” or: “Child, if you eat too much of this, the doctor will come and give you bitter medicine, or even put blood-sucking leeches on you!” The result is that, when the doctor enters the room under such conditions, the sick little angel starts to howl, to struggle and to kick around. An examination of the patient is absolutely impossible and for hours the doctor cannot do the soothing, relaxing thing. A sheet of paper and a pencil usually helped me quickly: One of the stories in the book is quickly invented, drawn with three strokes, and told as vividly as possible. The little wild opposition man becomes calm, the tears dry, and then the doctor can easily do his duty. |

|

So entstanden die meisten dieser tollen Szenen, und ich schöpfte sie aus vorhandenem Vorrate; einiges wurde später dazu erfunden, die Bilder wurden mit derselben Feder und Tinte gezeichnet, mit der ich erst die Reime geschrieben hatte, alles unmittelbar und ohne schriftstellerische Absichtlichkeit. Das Heft wurde eingebunden und auf den Weihnachtstisch gelegt. Die Wirkung auf den beschenkten Knaben war die erwartete; aber unerwartet war die auf einige erwachsene Freunde, die das Büchlein zu Gesicht bekamen. Von allen Seiten wurde ich aufgefordert, es drucken zu lassen und es zu veröffentlichen. Ich lehnte es anfangs ab; ich hatte nicht im Entferntesten daran gedacht, als Kinderschriftsteller und Bilderbüchler aufzutreten. Fast wider Willen wurde ich dazu gebracht als ich einst in einer literarischen Abendgesellschaft mit dem einen meiner jetzigen Verleger gemütlich bei der Flasche zusammensaß. Und so trat das bescheidene Hauskind plötzlich hinaus in die weite offene Welt und machte nun seine Reise, ich kann wohl sagen, um die Welt, und ist heute seit einunddreißig Jahren bis zur hundertsten Auflage gelangt. Von Uebersetzungen ist mir bis jetzt eine englische, holländische, dänische, schwedische, russische, französische, italienische, spanische und eine portugiesische (für Brasilien) zu Gesicht gekommen.

|

That's how most of these great scenes came about, and I drew them from what I had on hand; some were invented later, the pictures were drawn with the same pen and ink that I had first used to write the rhymes, all directly and without any authorial pretense. The booklet was bound and placed on the Christmas table. The effect on the boy who received the present was as expected, but the effect on some adult friends who saw the booklet was unexpected. I was asked from all sides to have it printed and published. I refused at first; I had not even remotely thought of appearing as a children's writer and picture book author. I was persuaded to do so almost against my will when I was once sitting comfortably over a bottle with one of my current publishers at a literary evening party. And so the humble house child suddenly stepped out into the wide open world and has now made its journey, I can well say, around the world, and has now reached its hundredth edition in thirty-one years. So far I have come across translations in English, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese (for Brazil). |

|

Ich muß dabei auch des sonderbaren Erfolges erwähnen, den das Büchlein anfangs in Frankfurt selbst hatte. In den ersten Monaten des Jahres 1846, nachdem der Struwwelpeter am vergangenen Christfest zum erstenmal in die Kinderwelt getreten war, wurde ich oft von dankbaren Müttern oder entzückten Vätern auf der Straße angehalten, welche mich mit den Worten begrüßten: “Lieber Herr Doktor, was haben Sie uns eine Freude gemacht. Ich habe da zu Hause ein dreijähriges Kind, welches sich bis jetzt sehr langsam entwickelte und nun in ganz kurzer Zeit das ganze Buch auswendig weiß und ganz allerliebst hersagt. Ich versichere Sie, in dem Kinde steckt was!” – Damals waren die Genies unter den Kindern ganz gemein geworden. Später sahen freilich die Leute ein, daß es nicht sowohl in den außergewöhnlichen Anlagen der Kleinen, als in der glücklich getroffenen plastischen Diktion steckte. |

I must also mention the strange success that the booklet initially had in Frankfurt itself. In the first few months of 1846, after Struwwelpeter was first introduced to the world of children last Christmas, I was often stopped in the street by grateful mothers or delighted fathers who greeted me with the words: “Dear Doctor, what a pleasure you have given us. I have a three-year-old child at home who has developed very slowly up to now and now knows the whole book by heart in a very short time and recites it very lovingly. I assure you, there is something in that child!” — At that time, the geniuses among the children had become quite mean. Later, of course, people realized that it wasn't so much in the little one's extraordinary talents as in the happily achieved graphic diction. |

|

Trotzdem hat man den Struwwelpeter aber auch großer Sünden beschuldigt, denselben als gar zu märchenhaft, die Bilder als fratzenhaft oft herb genug getadelt. Da hieß es: “Das Buch verdirbt mit seinen Fratzen das ästhetische Gefühl des Kindes.” Nun gut, so erziehe man die Säuglinge in Gemäldegalerien oder in Kabinetten mit antiken Gypsabdrücken! Aber man muß dann auch verhüten, daß das Kind sich selbst nicht kleine menschliche Figuren aus zwei Kreisen und vier geraden Linien in der bekannten Weise zeichne und glücklicher dabei ist, als wenn man ihm den Laokoon zeigt. – Das Buch soll ja märchenhafte, grausige, übertriebene Vorstellungen hervorrufen! Das germanische Kind ist aber nur das germanische Volk, und schwerlich werden diese National-Erzieher die Geschichte vom Rotkäppchen, das der Wolf verschluckte, vom Schneewittchen, das die böse Stiefmutter vergiftete, aus dem Volksbewußtsein und aus der Kinderstube vertilgen. Mit der absoluten Wahrheit, mit algebraischen oder geometrischen Sätzen rührt man aber keine Kinderseele, sondern läßt sie elend verkümmern. – Und wie viele Wunder umgeben denn nicht auch den Erwachsenen, selbst den nüchternsten Naturforscher! Dem Kinde ist ja alles noch wunderbar, was es schaut und hört, und im Verhältnis zum immer noch Unerklärten ist überhaupt die Masse des Erkannten doch auch nicht so gewaltig. Der Verstand wird sich sein Recht schon verschaffen, und der Mensch ist glücklich, der sich einen Teil des Kindersinnes aus seinen ersten Dämmerungsjahren in das Leben hinüber zu retten verstand. |

Nevertheless, Struwwelpeter has also been accused of great crimes, of being too fairytale-like, and the pictures have often been criticized harshly enough for being grimacing. It is said: “The book spoils the aesthetic feeling of the child with its grimaces.” Well, let's educate babies in picture galleries or in cabinets with antique gypsy prints! But one must also ensure that the child does not draw little human figures from two circles and four straight lines in the familiar way and is happier doing so than if one shows him Laocoon. — The book is supposed to evoke fabulous, gruesome, exaggerated ideas! But the Germanic child is only the Germanic people, and these national educators will hardly eradicate the story of Little Red Riding Hood, whom the wolf swallowed, of Snow White, whom the wicked stepmother gassed, from the popular consciousness and from the nursery. Absolute truth, algebraic or geometric propositions, however, do not stir a child's soul, but leave it to wither away miserably. — And how many wonders do not surround the adult, even the most sober naturalist! For the child, everything he sees and hears is still wonderful, and in relation to what is still unexplained, the mass of what is known is not so enormous after all. The intellect will already do itself justice, and man is happy who has been able to save a part of the child's sense from his first twilight years into life. |

|

Meine weiteren Bücher der Art, “König Nußknacker,” “Im Himmel und auf der Erde,” “Bastian der Faulpelz,” “Prinz Grünewald und Perlenfein,” entstanden in derselben Absicht und aus derselben Ansicht. Immer aber ging ich von der Ueberzeugung aus: “Das Kind erfaßt und begreift nur, was es sieht.” |

My other books of this kind, “King Nutcracker,” “Prince Grünewald and Perkensein,” were written with the same intention and from the same point of view. But I always proceeded from the conviction: “The child only grasps and comprehends what it sees.”

|

* This refers to a contemporaneous children’s story in which a boy named Fritz, out walking with his father, says he has seen a dog bigger than a horse. The father says they will soon come to a bridge where there is a large stone and that anyone who tells lies will fall and break a leg there. Fritz gets more nervous as they walk, and the dog gets smaller and smaller as he repeats his story, until – “Fritz! Fritz! The bridge is coming!” – he admits that the dog was no larger than most dogs. |

| |