|

Gerhard Wilhelm Mueller: Boo-Boo

Gerhard was the most reclusive and enigmatic of Ernst and Helen’s children. He served ever-smaller Lutheran parishes in Nebraska and northern Minnesota, subsisted below the poverty line for much of his adult life, and seemed only at home when he arrived — most often unannounced — to visit siblings. His siblings called him Gene (derived from a high school principal’s misunderstanding of “G. Mueller”) or Päsel; to neices and nephews, he was always Boo-Boo. No one really knew why.

His father’s pride and joy

Opa Mueller, twice disappointed and not subtle about it, finally had a son on December 4, 1904. Oma had little Gerhard’s photo taken for Opa’s birthday, but the surprise was ruined when another customer met Opa on the street and said, “I see your boy had his picture taken in his rubber boots.”

Chalmers Photography, Madison, Minn.

Gerhard was born in Madison, Minnesota, but moved to Freedom Township with his family when he was six years old. He had a happy childhood, according to his sister Frieda, but had little interest in rural living. He did not learn to milk a cow until he was in high school, and in an age when rural Lutheran ministers were often paid in kind, he never owned so much as a single chicken. (Opa, by contrast, butchered hogs, received and kept chickens and dairy cows, and tended a substantial garden.) What Gerhard loved was cars, a rarity in the early days at Freedom.

When he was 13, Gerhard’s parents enrolled him as a high school student at Concordia, St. Paul. He did not want to leave home. “Dad did not ask me whether I wanted to go to this school at all,” Gerhard wrote in a journal of random jottings near the end of his life. “He and mother packed a trunk full of belongings and cranked up the nickel-plated Model-T Ford and put me and the trunk in the back seat, and so we’re off.”

Gerhard was lost and miserable, flustered by common non-rural tasks like finding the post office — and he was poorly prepared for the academics. (The oldest Mueller children received “barely mediocre” instruction at the one-room schoolhouse in Freedom, according to his sister Frieda.) He found Concordia poorly run, supervision lax, and life in the dormitories cruel and “un-Christian.” He stuck it out for two years, then simply walked away — fled — in his third year. His sister Erna found him sitting in the chicken coop, gathering strength to speak with his father. Opa did not force him to return; Gerhard finished his studies at Waldorf Consolidated High School, where he played basketball and graduated as valedictorian.

In the summer of 1924, Gerhard struck out on his own, planning to hitchhike to California. He sent a postcard home from Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and made it to York, Nebraska, about 40 miles west of Lincoln, where he ran out of money and enthusiasm. He turned back for home and arrived at Freedom in late July. That fall, he entered Doctor Martin Luther College in New Ulm, intending to become a Lutheran teacher. Men who studied to become teachers received free tuition at DMLC then. He did well with his studies, except for music, as dutifully noted on his

diploma. Largely because he could neither conduct a choir nor play the organ, he received a difficult placement at a one-room school in Lake Mills, Wisconsin, upon graduation in 1926.

The 1926-27 DMLC catalog lists Gerhard as a second-year normal student (p.41), Adelheid as a student in the 11th grade (p.44), and Frieda as a Class of ’25 graduate (p.55). Gerhard hated teaching. He could not keep order and had an acute sense of failure. “One day, I just let them go,” Gerhard later wrote in a journal, “and just when the cyclone was at its worst, in came the superintendent ... and me standing there shooting paper arrows. ... I have never lived that down.” Before the year was over he was begging Opa to send him to Concordia Seminary in Springfield, Illinois, which Opa did.

Seminary graduate

Gerhard graduated from Concordia Seminary, Springfield, in the class of 1930. His friends remembered “Pongo” at the 35th reunion, which Gerhard attended.

Gerhard graduated from the seminary in 1930 and received the poorest placement among all the calls — to a congregation with 13 voting members about a mile outside Grafton, Nebraska. (The Wisconsin Synod church was in Grafton proper.) The Dust Bowl struck, killing off the lawn, shrubs and fruit orchard at the parsonage. Gerhard had horrific hay fever. With his farming parishioners unable to make a living off the land, Gerhard attempted to increase the little congregation by canvassing several nearby townships in a small mobile chapel. The portable chapel worked for a while and received honorable mention in the district. He also wanted to start a school, but his D.M.L.C. diploma was not state-accredited. Gerhard enrolled at Seward Teacher’s College and earned a diploma that was recognized by the state of Nebraska.

Gerhard’s sister Frieda mentioned a few women in his life. Gertie King, with blond curly hair, was a fellow student at Seward. Frieda believed this to have been entirely platonic — perhaps Gerhard admired from afar, perhaps he asked her out and she refused — but Gertie King was a name neices and nephews heard even decades later. Annie Winter was more serious. Gerhard drove home from Nebraska just for a date and once drove on to La Crosse, where Annie taught school. They also met and dated in Janesville when Annie was home visiting her family. Frieda felt Gerhard rushed things. He proposed; Annie said no. A year later, Annie reconsidered and tried her best to re-establish contact, but Gerhard appeared to have given up on the whole idea of marriage, according to Frieda.

After about 10 years in Grafton, Gerhard accepted a call to a larger congregation in Cordova, with the proviso that he could return to Grafton twice a month and preach for the six or seven voting members who still remained there. Gerhard was financially better off, and the congregation built a new church. But Cordova was also a gossipy small town. There were two kids in his Sunday School whose widowed mother was a cross-country truck driver. Gerhard looked in on the kids frequently, especially when their mother was out on the road. Gossips soon linked Rev. Mueller with the widow, who had a poor reputation in town, and Gerhard’s life became quite difficult. In 1948, following Opa’s death in August, Gerhard accepted a call to Tenstrike, Blackduck, and Moose Park, Minnesota.

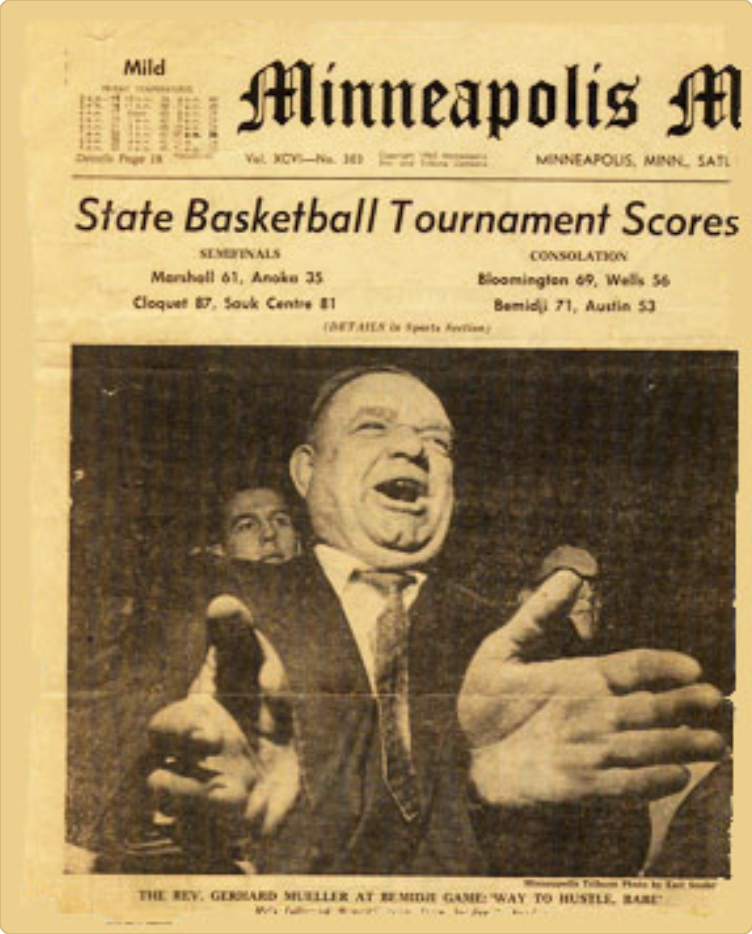

Way to hustle, babe!

Gerhard’s winter diversion was the Bemidji high basketball team. When they made it to the state tournament, the kids on the team chipped in to get Gerhard a bus ticket.

Photo by Earl Seubert / Minneapolis Tribune

Northern Minnesota was kinder to his hay fever, but it was brutal in other ways. His predecessors at Tenstrike — Rev. Herbert Motzkus and Rev. A.A. Diercks — were both unmarried and appear to have been bitter enemies. Diercks had accused Motzkus of being engaged to two women at the same time and sought to have him removed from ministry — which Diercks was able to do when he became circuit counselor. Diercks also became a bitter enemy of Gerhard and cultivated a dissident group within Gerhard’s congregation at Blackduck, which included some of Diercks’s in-laws. There were agitations behind the scenes, gossip, disgust at Gerhard’s lifestyle (he could not afford electricity, so the power was turned off at the parsonage) and a few very angry congregational meetings.

Much to his brother Herbert’s disgust, Gerhard offered to resign at Blackduck during a brutal congregational meeting August 24, 1954, chaired by Diercks and Rev. A.C. Seltz. After order was restored, Diercks asked the congregation to keep Gerhard on staff until January 1, 1955, so he would qualify for some sort of compensation. (Gerhard never officially resigned at Tenstrike but took a leave of absence. The congregation later disbanded and Gerhard bought the church.)

Gerhard lived with his sister Frieda and his mother in Eagle Lake, Minnesota, from May 1955 until January 1, 1956. Friends among the clergy lobbied for his return to the active ministry, and Diercks finally agreed that Gerhard could take a call elsewhere. (Oma wondered what was going on: “Was für ein Schuft ist der Diercks?" [What kind of scoundrel is this Diercks?], she asked Boo-Boo.) Gerhard returned to service on a missionary basis at small Missouri Synod congregations, including Lake George, Bagley, Park Rapids (rural), Dryden, Ontario, and Sebeka. For his last 13 years, beginning in 1957, he served four congregations: Height of Land, Ponsford, Evergreen, and Frazee Township.

He also succeeded in restoring Herbert Motzkus’s good name, refuting the slanders, and getting Motzkus reinstated to the LCMS ministerium — with retirement benefits.

A note on the obituary (linked, above left): Although he had been a hardy person for most of his life, Gerhard’s health began to fail in the late 1960’s. Obesity, swelling in the extremities and possibly congestive heart disease or undiagnosed pre-diabetes led him occasionally to the Wunderdoktoren in Fargo. His letters suggest that he knew he would not live long. The obituary ran in the Becker County Record on Thursday, September 10, 1970, page 5. There are a few errors. Gerhard actually arrived in northern Minnesota in 1948; his failed tenure at Tenstrike and Blackduck is ignored. His brother was Ernest, not Earnest; his sister was Frieda, not Freda; his sister Adelheid was Mrs. Hilbert Nickel, not Mrs. Henry; and his sister Norma, oddly, was not mentioned.

A note on Gerhard’s journal: In November 1980, I drove through northern Minnesota, gathering what materials I could. I found one man who had carted off several boxes of Gerhard’s junk. In the pile was a cheap dimestore ledger in which Gerhard had written several vignettes. They are in pencil, and the handwriting suggests poor lighting, failing eyesight or both. The entries are undated, but I found a flyer for a “Bible-Science Seminar” offered by the Springfield seminary in July 1968 inside the ledger book, possibly used as a bookmark. My guess is that Gerhard wrote this in his last year of life (1969-70), as if trying to keep his mind sharp.

|