|

Winke für Auswanderer: Hints for Emigrants

Carl, his brother Richard, and nephew Eduard began their trip to New York by river steamer from Düsseldorf to Rotterdam, and by sea from Rotterdam to Havre and Cherbourg. It was an early introduction to seasickness, poor service, inedible food, overcharging, and too much baggage. Still, he encouraged others to make the trip.

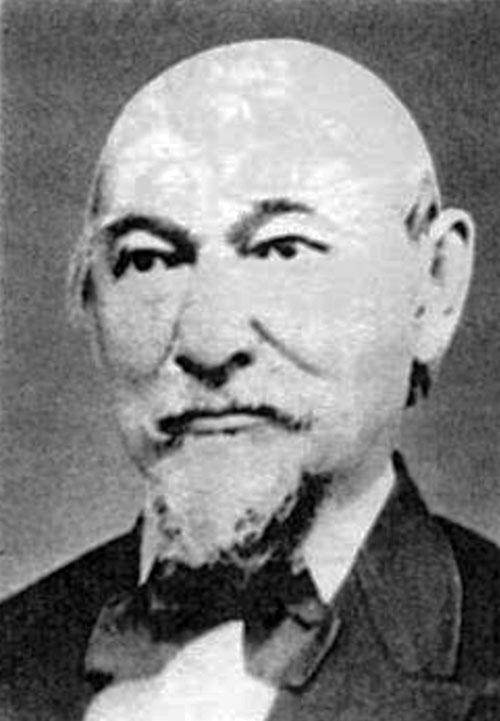

Carl de Haas

8 August 1817 – 21 April 1875

Preface to the First Edition

Upon my departure from Germany I promised friends and acquaintances that I would send them, within the year, a complete report of my observations during the journey from Elberfeld, Germany, to Calumet, Wisconsin, and particularly of my experiences here.

I have now been in Wisconsin a quarter of a year, and it is time to fulfill, to the best of my ability, that promise. It is, of course, rather presumptuous that I, a young farmer in the midst of activities that harmonize badly with writing, should take up the pen with a hand rough and stiff from the unaccustomed work. I would have preferred to let my observations have time to mature. But there is one thought that outweighs all considerations which might work against my promise: I hope to be useful to my friends with this report, to prevent some from overhasty steps, and perhaps to encourage many to come over and share our lot.

As I know from earlier experience, a letter from America is soon read to shreds, especially on the poor paper one gets here. I prefer therefore, to have these pages printed. Perhaps other countrymen beyond my circle of acquaintances will draw valuable advice from these hints.

— Dr. Carl de Haas

Calumet, October 23, 1847

Hints for Emigrants

I. Leaving Germany

In 1844, toward the end of my student years in Berlin, I and two young men who were my close friends decided to emigrate to America. Our goal was Texas; the so-called “Nobles’ Association” was to make the arrangements for our emigration. Everything had been considered and arrangements had been made, when we read some reliable reports and letters which convinced us that Texas, beautiful and rich as the country is, could not in its present state be a goal for the emigrant who seeks a peaceful, free life in nature, not merely adventure. The hostility of the numerous Indians there has to the present day prevented emigrants transported there from taking possession of the land sold to them, and even the cities which have been laid out are by no means safe from their robbing attacks. Furthermore, the climate is tropical, which is not favorable to the German constitution, and the higher spots where the climate is more bearable for us, are surrounded by unhealthy regions. Perhaps the Nobles’ Association will be in a better position, when the Mexican War is over, to fulfill their promises thus far so poorly kept. Then perhaps the new state of Texas will be safer and will be a really livable place for the emigrant who finds the German climate too cold.

To be brief, our plan fell through. I joined the faculty of my home town (Elberfeld) vocational and high school as temporary teacher of mathematics and chemistry, and the once serious plans to emigrate vanished from my thoughts.

To be brief, our plan fell through. I joined the faculty of my home town vocational and high school as temporary teacher of mathematics and chemistry But my hopes were not to be abandoned permanently. In the fall of last year several young men in Elberfeld worked together to get information on the best goal for German emigration. On the second Christmas day 1846 I met some of them and joined their group. From that time on my resolve was unshakable, although I had to keep my plans secret up to a few weeks of my departure because of my teaching position. A letter printed in the Barmen newspaper, written by an emigrant from Wesel to his family, first called our attention to Wisconsin and to the region around Milwaukee. Other letters from an emigrant, Johann Mentis of Friesdorf near Bonn, praised Fond du Lac county and the Calumet colony, to the north of Milwaukee, as being a place especially suited for German settlement.

Several members of our society tried to sell their possessions but found no buyers because of the extremely bad times in Germany and had to put off their departure. The time of departure was so delayed for others that in May only eight men, three women, and five children prepared to leave. And then even these divided. Two men with their wives and three children (Cabinet maker F. and the Stonemason K.) departed the beginning of May. They took cabin passages on the three-master Flora from Antwerp and were very satisfied with their 32-day trip. They could not praise highly enough the captain’s good treatment of them, as well as the behavior of the crew, and they judged as excellent their food and drink at the captain’s table.

With my brother Richard, engraver and modeler; my nephew Eduard, brewer; Büttner, agriculturist; Langefeld, baker (all unmarried), and the clerk Kohl and his wife and two children, I began the long journey on May 17. We had made reservations 14 days previously in Elberfeld through the agent of the well-known Dr. Strecker for the first of the three French steamers which were to make the voyage to New York twice a month from the middle of May on.

The afternoon of May 17 while I sat with my brothers and friends in a public resort outside of the town, the agent sent us tickets for the steamer leaving that same evening from Düsseldorf, reporting that he had just received them from Dr. Strecker. Anyone who has ever got ready for such an important trip will be able to imagine our terrible situation. It is a real miracle that we arrived at seven o’clock in the evening all packed at the Düsseldorf-Elberfeld station. Of course, the parting from parents and brothers and sisters was cut short. I saw my father barely long enough to say farewell. Some chests had still to be packed and marked, and Prussian money exchanged for French. It was very pleasant for us that the news of our departure had quickly made the rounds and that almost all of our friends could gather at the station. We drank farewell with one glass of May-punch — Maitrank, white wine flavored with woodruff or asperula odorata (perhaps the last for us). With the general cry of “Hurrah, America” and the waving of hats from the windows of the moving train, we lost sight of the homeland.

Confirmed Americans as we already were, still a melancholy feeling seized us as we flew for the last time in the evening twilight through the beautiful valleys of the Wupper. This feeling persisted until it was driven away by concern for our baggage in Düsseldorf. My belongings were most carefully packed with those of my brother and nephew in 14 smaller and larger chests. Although we were three, we had to pay 9 Thaler excess baggage on the Düsseldorf steamer. Our contract read: “Düsseldorf to New York, meals included, 98 Prussian Thaler.” From Havre to New York the trip cost 300 Francs, which is 80 Thaler, therefore the trip from Düsseldorf to Havre cost 18 Prussian Thaler. Usually one expects to do better by signing a contract with agents; here the bitter opposite was true. We could have made this trip at our own expense for less than half of that sum if we had wanted to travel in the manner that Dr. Strecker arranged. The conductor of the Düsseldorf Viktoria, as a special favor, let us have first class; the dining-room manager, however, would not let us have the meals of that class, as he maintained that only 1 Gulden had been paid him by Dr. Strecker. We had to reconcile ourselves, therefore, to a surcharge of 10 Silbergroschen per person. Our baggage was sealed after leaving Düsseldorf and did not have to be inspected at the Dutch border. The baggage inspection of the other passengers lasted about an hour, during which time we emigrants were left to wait out on the river bank.

I am warning my compatriots against the elegant vagabonds who force themselves upon travelers at docks and stations in Europe as well as America Upon arriving in Rotterdam, we looked up the inn which Dr. Strecker had recommended through his agent. It was, however, such a low-class pub and the bedrooms with their poor and dirty beds greeted us with such an unpleasant odor that we left at once, without even taking off our coats. After we left that den, we decided to go to the first and best inn we could find. We soon found such a place opposite the dock of our Rhein steamer, the Hotel des Pays Bas. As we were about to enter, the street-boy accompanying us called our attention to the fact that the king usually stopped there. This remark, spoken in a warning tone, irritated us to bold defiance, and we entered and got splendid rooms. Although the innkeeper and waiter looked somewhat surprised, we were well and attentively served. The bill also was in order: We had to pay 5 Thaler Prussian per person for one day and two nights.

The steamer Rotterdam was to take us from Rotterdam to Havre. We presented ourselves to the proper agent who claimed at first to know nothing about us, but after some hesitation gave us tickets for the trip to Havre. The baggage was free for this trip. We began to realize in Rotterdam that the large amount of baggage we had with us was a frightful burden. We stayed a day and a half in Rotterdam, but on account of our baggage had scarcely half a day to see the big commercial city. An emigrant must never take his eyes off his baggage as long as it is not in complete safety, and that is only the case when it is down in the ship’s hold or when the customs officials have it under lock and key. I must warn the innocent German emigrant of the greediness of the Dutch; those people can never ask enough, and even when one gives generously, they are never satisfied.

On the Düsseldorf steamer we found some traveling companions who wanted to go with us to Havre and to New York. As soon as we landed, a neatly dressed young man introduced himself to them as a waiter on the steamer to Havre, and he stayed near them. He led us into a very poor beer-saloon outside the city, whose owner he seemed to know very well, and on the way mentioned all sorts of advantages he could get for us on the steamship. Among other things, he hinted that he would be able to get each of us one of the beds intended for the immigrants. My party and I did not involve ourselves because he seemed suspicious to us from the first; the others tried to win him by treating. At our departure at three o’clock at night, this waiter was not to be found, and on inquiry we learned that this strange ship had no waiters at all.

I am warning my compatriots against the elegant vagabonds who force themselves upon travelers at docks and stations in Europe as well as America, hold one up with questions and tell all sorts of interesting things. As a rule such people mean no good.

Immediately after we embarked, all the small hand baggage of the passengers, including the most indispensable daily necessities, was thrown helter-skelter in a hole in the hold, and not given out again until we lay at anchor in Havre. The only reason for this could be, as I see it, that the captain wanted to leave as much room as possible on deck, where we could stretch out during the attack of sea-sickness which was soon to come. The explanation for this is as follows: The ship Rotterdam was no larger than the Rhein steamers and took about 350 passengers aboard. In the only cabin (there was only one class on the boat) there was just space for about 50. The others had to camp on the deck. Anyone who has seen such a sea ship knows just how much space is left for passengers.

Out of every 100 at least 96 lay around on deck ... or leaning overboard, committed the contents of their stomachs to the creatures of the sea At eight o’clock in the morning of May 20th, we reached the high seas. Most of us were seeing it for the first time and stood deep in solemn observation of the endless mass of water before us. Some, (especially women) were soon torn away from these serious reflections by the symptoms of seasickness. These people were at first laughed at, but soon one after another of the laughers found himself in the same position. On top of that, the sea began to be rough about noon, and the ship rocked so violently, that out of every 100 at least 96 lay around on deck as though unconscious, groaning, or leaning overboard, committed the contents of their stomachs to the creatures of the sea. They lay, one beside another on the hard deck, for our blankets had also been thrown in the hole. There was no sign of beds on our ship, I was very glad that in my great misery one of the sailors who were sweeping around us with brooms (we called them cowstall hands) was so gracious as to offer me his bed for five francs. I had just enough human consciousness left to squeeze the price down 1 franc. How I got to the bed, and what went on during the 16 hours I spent in it, I cannot say. I can only remember dimly that upon awakening, the ship creaked terribly and that bedbugs and fleas had bitten me badly.

The morning of May 21st I woke up in a narrow, rectangular hole, which had disgustingly dirty sailors’ beds all around on the walls. I was in one of them. In the person climbing out of the bed above me I recognized my friend L. who had shared my fate. The sailors who gave up their beds to us were sleeping in front of us on the floor, A pestilential stench filled the room, I could not stay there a moment longer after returning to consciousness. As bad as my sleeping-place had been, I could nevertheless say I had had luck compared with the others, for they, lying all this time on deck, had been soaked by the sea- water splashing up on deck; as a consequence, their faces began to itch unbearably and the skin became lobster-red and peeled.

As one can gather from the above, I had a rather bad attack of sea-sickness, and I had another later. Nevertheless, I maintain that it would be foolish for anyone to let himself be prevented from taking the trip because of fear of this rather drastic emetic treatment (for that is really all it is.) In most books this sickness is depicted too luridly. It is indeed a sad spectacle to see so many people lying about in deepest abasement, all sense of shame forgotten, like cattle in their own dirt. But this spectacle does not make the disease any more dangerous. No one dies of it; to the contrary, once the suffering is past, they are all, without exception, much healthier than before, and they experience an appetite such as they have never known before. Only, it was a shame in our case, that there was so little opportunity to satisfy this unheard-of appetite. The meals on board were in the hands of a Jew, whose dirty little boy, his coat shiny with pitch, stood before a large kettle and distributed its contents in earthenware bowls among the 350 passengers who were almost fighting to get it. This was a dirty gray-white brew, which they passed out as coffee; I could not drink it, partly because of the bad taste, partly because of the extremely unclean manner of serving. But in contrast, a piece of the splendid smoked meat which we had brought from home, tasted just so much better with the dry bread they gave us.

This was a dirty gray-white brew, which they passed out as coffee; I could not drink it

I advise every emigrant to take some pieces of good beef even when meals are provided, for in an emergency this will give him welcome nourishment. All other edibles should be left home, particularly baked goods, (except ginger-cakes). Of course, one may take food along for the first two days of the trip, but when packed in chests, food soon spoils.

I shall not describe the French coast along which we sailed; this is the concern of the European travel writer. It could scarcely be expected that I, sick of Europe as I was, should tarry there longer than is necessary to describe to my countrymen the unscrupulous treatment their emigrating brothers suffer while still in the old country.

On May 22nd toward noon the beautiful coast of Normandy came in sight, and at the same time the gathering of hungry passengers told me that the Jew was ready with dinner. Of what did this first French dinner consist? (In my misery I had not thought of dinner the previous day.) It consisted again of a piece of bread, with which we received a piece of dry and very poor beef-steak in our hands. That was all. I inquired why they did not supply at least knife, fork and tin plate. My answer came: They had done that in the past, but that the emigrants had carried such utensils off without paying for use in their log cabins. Whether this unpleasant accusation is true or not, I do not know, but they should at least have told the rather easily disgusted emigrant through the agents, that one receives only the food and no eating utensils. We had various eating implements with us, but they were locked up in the hole with the traveling bag.

We were however so fed up with the stay on the Rotterdam that we preferred to be taken to shore immediately in a small boat

The captain did not trouble himself about the passengers, except occasionally on his walks to send a passenger lying on deck out of his way with a kick. In brief, this trip was one of the most horrible that one can take, and Dr. Strecker in Mainz may take up with his own conscience the fact that he could offer us such a trip for 18 1/2 Thaler. On account of ebb tide, our steamer could not enter the harbor until evening of the twenty-second; we were however so fed up with the stay on the Rotterdam that we preferred to be taken to shore immediately in a small boat.

Hardly had we arrived on land than the customs pounced upon our small baggage, dragged it into the customs house and investigated it into the farthest corner. A tin of gunpowder was confiscated; the quantity of tobacco we had brought was however not too large to be taken. I noticed here, how my little bit of French helped. I advise that no one who does not understand something of the French language himself at least have a dependable man in his company who can make himself understood to the people traveling via Havre or on a French ship. Otherwise one can get into the greatest difficulties, into the hands of the German innkeepers, who are not usually the best. One is everywhere in danger of being taken at a disadvantage. We stayed in Havre at the Hotel de Paris near Santune close to the harbor. The room and service were very good, but cost us nearly 6 francs a day.

Our trunks were put under bond and locked up, and therefore we did not have to open them.

Carl de Haas and Winke

Top of File

II. In Havre and Cherbourg

|